Zelda D’Aprano’s chain-in drew attention to the Equal Pay Campaign in 1969. But what details of this famous protest have not been so well remembered?

The 21st October, 2019 will mark the 50th anniversary of Zelda D’Aprano’s famous chain-in to the Commonwealth Building.

This protest aimed to draw attention to the Equal Pay Case that was presented by the Australasian Meat Industry Employees Union.

This case was being tested by the Commonwealth Conciliation and the Arbitration Commission, as well as the wider Equal Pay Campaign in 1969.

Earlier this year Dr Clare Wright posted on Twitter that a statue of D’Aprano should be built on “the site of her courageous stand.”

The tweet seemed to be a success, gathering over seven hundred likes and more then two hundred retweets. Just four days after posting her Tweet, Wright tweeted “operation #Zelda is go!”

We can’t dispute the importance or significance of commemorating D’Aprano and the contributions she had made towards the Union and Women’s Liberation Movements.

Perhaps, we still need to question what is being commemorated and what details have been excluded in this historic event.

Reflecting on a bold life

D’Aprano indeed lived a remarkable life.

Her autobiography, which was originally published in 1977 under the title Zelda: Becoming a woman and had been republished in 1995 under the title Zelda.

It begins with her impoverished childhood, growing up in what she described as the “slum area of Carlton”.

Moving on through her life, the autobiography discusses her early departure from school and subsequent commencement of her employment as a factory worker, being married at sixteen and a mother by eighteen.

D’Aprano seamlessly demonstrated how the personal and political life intersected.

As her book explores her harrowing experiences of sexual violence and abortions at the hands of unkind and exploitative doctors, her involvement in the local communist party and union branches, the break-down of her marriage and her concerns about her health.

Refusing to remain silent, D’Aprano puts forward the discrimination that she had experienced.

She details the hostility and discrimination she had experienced by members of the communist party and union groups, to her departure from and her increasing involvement in the Women’s Liberation Movement.

Resisting the traditional historical narrative

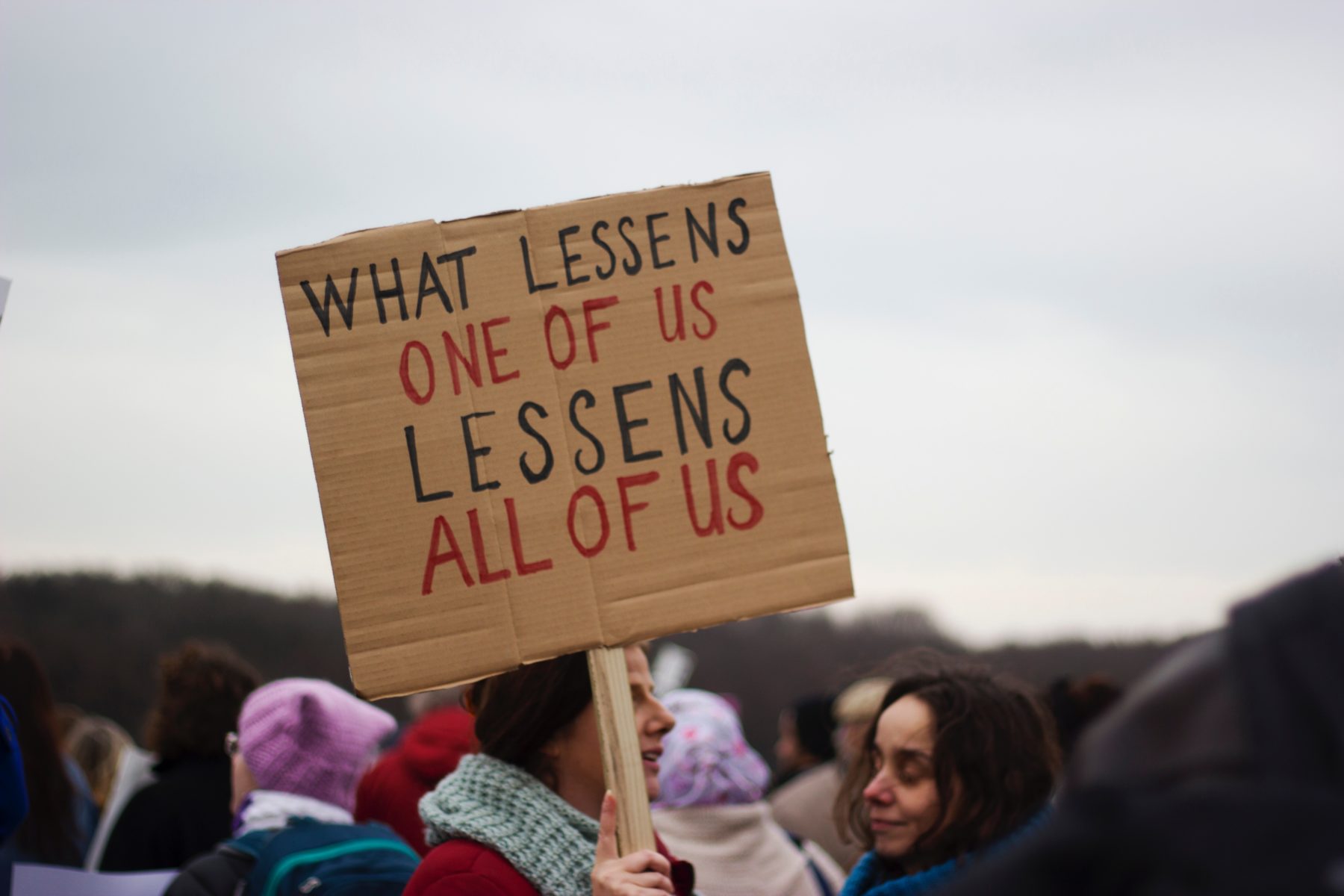

When some remember D’Aprano’s famous chain in, they often think of her press picture, in which she stands alone, chain wrapped around her waist and holding a sign that reads “NO MORE MALE AND FEMALE RATES. ONE RATE ONLY.”

But D’Aprano’s chain-in wasn’t a one-woman protest, as some historical narratives have lead us to believe.

In her autobiography, she described the way that “several” women had accompanied her to the Commonwealth Building.

While these women did not chain themselves, D’Aprano contended that they “walked up and down with placards which called upon the government to grant women equal pay.”

These women have not been named in D’Aprano’s autobiography, and in many respects their contribution to the fight for equal pay has been lost.

Who is remembered?

Dr Margaret Henderson, who is currently a senior lecturer in Literary Studies at the University of Queensland in the School of Communication and Arts, has been critical of the historical accounts detailing Women’s Liberation Movement in Australia.

In an article co-authored with Professor Margaret Reid, Henderson questioned how narratives centred around the Women’s Liberation Movement in Australia have been constructed.

Henderson and Reid scrutinised the way historiographies and autobiographies of the Women’s Liberation Movement have shaped the collective identity of the Movement.

Ultimately affecting the way that the Movement has been remembered.

D’Aprano’s autobiography does provide valuable insights to her life and her experiences in relation to the Union and Women’s Liberation Movements in Melbourne.

However, if we place too much emphasis on her experiences alone, we risk losing the experiences of others and the insights that their experiences would contribute to this history.

Who were the women who protested with D’Aprano?

What did their placards say?

What experiences led them to protest alongside D’Aprano?

There is no debating that D’Aprano had taken a courageous stand fifty years ago by chaining herself to the Commonwealth Building to draw attention to the Equal Pay Case.

Even after she had resigned from the Communist Party and the Union Movement, D’Aprano continued to participate in the Women’s Liberation Movement.

There are traces of D’Aprano’s continued involvement in the Movement in the Melbourne Women’s Liberation Newsletter in which her name is printed alongside a fundraising event for women’s and feminist music; as a contact for her consciousness raising group and as a member of a group that was concerned with working women, to name a few examples.

It is important to remember that D’Aprano did not take her courageous stand alone.

In positioning D’Aprano as the only face of the fight for equal pay and gender equality we run the risk of losing the experiences and contributions of those who are not as well known, or well-remembered.