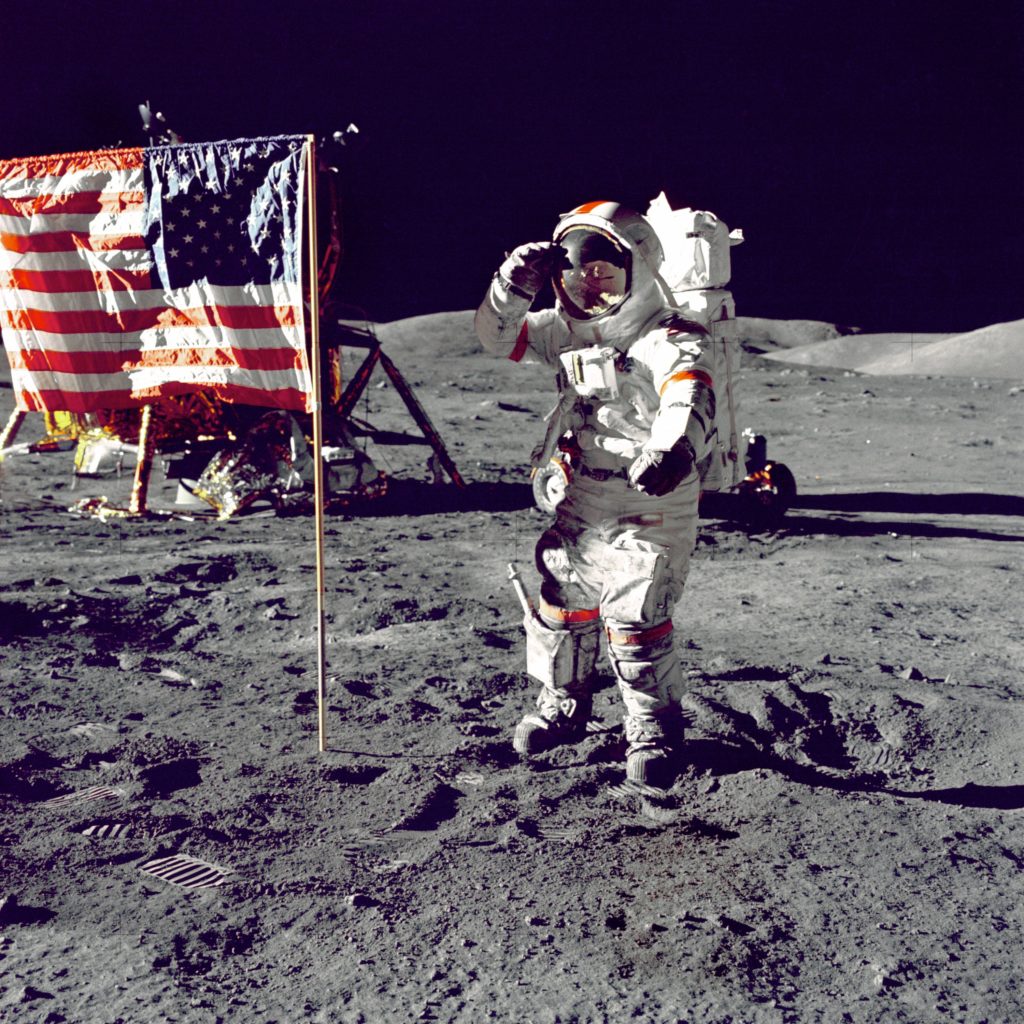

The 20th of July, 2019 marks the 50th anniversary of the first Moon landing. But humans have been captivated by the celestial body for much longer.

The Moon and us

“Thou silver deity of secret night”

In her poem, ‘A Hymn to the Moon’, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689-1762) described the Moon as a mysterious, ethereal force. In ‘The Embankment’, T. E. Hulme refers to the vastness of the night sky as being an ‘old star-eaten blanket’, ancient and overrun with bright balls of burning gas.

Dr Evie Kendal, a lecturer in Bioethics and Health Humanities in Deakin University’s School of Medicine, says we’ve always been fascinated by the Moon and its place within the empty vastness of the cosmos.

“I think humans have always looked to the sky for inspiration and a feeling of belonging to something bigger,” she says. “The Moon has a cultural and religious significance to many, in addition to controlling elements of our immediate environment in a tangible way.”

For instance, the Moon and the Sun work together to create tides in the ocean. The ocean that is facing the Moon is pulled towards the celestial body more than it is pulled towards the centre of the Earth.

This creates a high tide. A second high tide occurs on the opposite side of the Earth, as the ocean in the middle of the Earth is being pulled away from the centre and towards the Moon.

The Moon is also used to measure time. The Lunar calendar is ordered by its monthly phases and is used to inform the placement of dates for significant celebrations across global cultures and religious traditions, such as the Chinese New Year, the Islamic holiday of Ramadan and the Christian celebration of Easter.

United fascination

Dr Kendal says this global connection to the celestial body is part of what makes the first Moon landing so special for many people.

“It represented a collaborative human effort that served to promote a global sense of achievement in a really unique way,” she explains. “I think part of this was that shared fascination with the night sky and what it means for our own place in the universe.”

The first Moon landing gave us scientific insight into the lunar landscape, as well as what the Earth looked like from the perspective of another planet. But part of our relationship to the celestial body remains mysterious; there is an understanding that the Moon is something ethereal and impossibly distant, despite everything we know about it.

“The romantic attachment humans often have for the Moon hasn’t changed,” says Dr Kendal. “There are countless poems and love songs that reference the Moon and its beauty.”

For instance, Emily Dickinson (1830-86) famously described the crescent moon as being ‘a Chin of Gold’, vulnerable, but splendid.

Our ethical responsibilities

With our ability to access the Moon comes the possibility of using the planet’s resources for our own gain. Dr Kendal has written on the emerging field of space ethics, which aims to hypothesise and discuss the ways in which celestial bodies may be used or misused by humans in the future.

She even taught a class on consent for the use of celestial objects in 2015, which analysed possible interpretations of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty in terms of space travel, building human settlements, and the mining of resources. Questions related to what kinds of research we would allow on the Moon, and who has the authority to make these kinds of decisions, are also topics of interest.

In the wake of overpopulation and limited natural resources on Earth, some have investigated establishing human settlements on other planets, such as Mars and the Moon.

The practicalities of how we can conceivably transport humans there has taken precedence over some other pressing questions: would Moon-based humans have the same legal and human rights as those who are Earth-based?

Would anyone born on the Moon by Earth-based parents have a claim to citizenship on Earth, or would their only legal home be the Moon?

How would their bodies mature and grow in conditions that are vastly different to those on Earth, such as reduced gravity?

Dr Kendal says industrial and commercial possibilities also raise a plethora of questions. “Given the non-appropriable nature of celestial objects according to the Treaty, issues such as whether a nation state or private business can engage in off-world asteroid mining or tourism are interesting ethical questions.”

Dr Kendal says it’s important to have these discussions about how we may choose to use the Moon because of the way we’re currently misusing the Earth. There’s a strong possibility we won’t learn from the mistakes we’ve made on our planet and simply mirror them on another, such as overzealously plundering resources, and failing to protect and preserve certain environments.

“There is a serious risk that these practices will simply be repeated in space, with corporate interests being prioritised over ethical or environmental concerns,” she says.

To avoid this, it’s necessary to create a framework of rules and guidelines on what are and are not acceptable ways to use the Moon and its resources. Dr Kendal believe it’s vital that these guidelines be discussed and refined, beginning as early as possible.

“There is an opportunity now to establish ethical guidelines for the exploration and commercialisation of space aimed at avoiding the exploitative and colonial practices that have hurt so many Indigenous people groups and natural environments over human history,” she says.

Melina Bunting

Staff writer