Aileen Walsh, from Deakin University’s NIKERI Institute, on looking to the past to protect the future.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples should be aware that this article contains the images and names of people who have passed away.

For the past two and a half years I have immersed myself in various western knowledge systems, their scholarly disciplines and their theoretical genealogies to understand the various perspectives of the deep past.

At the same time, I have also endeavoured to decolonise my thinking by embedding myself within Aboriginal knowledge systems; reading Aboriginal stories from the deep past and identifying myself with awareness of how the frontal cortex operates on our decision making, within Aboriginal systems of governance via Aboriginal law and spirituality.

This may sound like a contradictory process, but it has been possible because I am Aboriginal.

The clearer understanding of how I think through a spiritual lens rather than western ideologies is possible because I was raised to be anti-colonial, to question whiteness, especially the British because my father was Irish.

But my mother also taught me to see the world through an Aboriginal lens with Aboriginal knowledges.

And I have immersed myself in the Daisy Bates archives to find the 18th and 19th century ancestors of 21st century Noongars.

From the beginning of my research into the deep past, I had to make my research relevant to the crisis of climate change and the destruction of life on earth.

I would argue all research must be directed at the crisis of the mass destruction of non-human life upon which human life depends.

For this reason, although I am looking at the deep past, I am also looking at the collision of the deep Aboriginal past with whiteness as colonialism and the mentalities that would rather ignore the ugliness colonialism has created rather than deal with it.

My research has had to be transdisciplinary to try and see the deep past as clearly as possible.

I have followed Daniel Lord Smail’s lead in On Deep History and the Brain and taken it one step further by looking at the role of language and how it frames our familial psychological and emotional psychohistories.

I have explored the various non-Aboriginal religious traditions and developed a view of whiteness along the lines of Lynn White’s hugely influential work, The Historical Roots of Our Ecologic Crisis, who noted back in 1967 that the mass destruction of non-human life can be seen as a product of the cultures of the Judeo-Christian or Abrahamic faiths.

Aboriginal law never changes

In tjukurrpa there is no time. There is only life in the past and future. It is possible to see the past and future at once, a sophisticated conceptual process that relies on what philosophers call ‘phenomenology‘.

Although days and lunar months and seasons are recognised and named, Aboriginal epistemologies see how humans are connected to the rest of life and celebrate, revere and adore all other life by acknowledging it as family.

In the tjukurrpa, the law does not change. The tjukurrpa has stayed the same for many tens of thousands of years.

This is an extremely important point to acknowledge: an unchanging set of laws for people all over the continent – who knew how they had to live or otherwise die – meant that an equilibrium of culture was maintained and sustained that cannot be seen anywhere else in the world.

This is a cause for celebration to realise that Aboriginal law was adhered to for the sake of the future generations.

Think about it.

Aboriginal people all over this continent lived by the same law. It had different names according to the language group, but all Aboriginal people lived by the same fundamental laws and thus values.

Aboriginal people all over the continent were related to each other according to the skin group they belonged to. The purpose of skin groups is to maintain proper relationships between people.

People in whiteness are unable to understand these laws and how they can be unchanging.

Even some Aboriginal people are so corrupted by the ways of whiteness they think the unchanging nature of Aboriginal law was backward because Aboriginal cultures were not evolving to the apex of cultural superiority held by whiteness.

Dark Emu by Bruce Pascoe attempts to make Aboriginal cultures more palatable by indicating Aboriginal people were beginning to follow the path to cultural evolution but ignores the length and strength of Aboriginal law.

‘Sciencing’ Aboriginal knowledge

Unchanging laws are the spiritual embrace Aboriginal people maintained with all life for over 60,000 years.

But it is since the end of the last ice age that the evidence of this spiritual tradition becomes more clearly visible: from the scientific ageing of Aboriginal memories maintained within the vast epistemological repertoire, passed down through many tens of thousands of generations.

Archaeologists and other scientists have been investigating Aboriginal epistemologies to find memories of changes in the environment.

Memories were passed on through thousands of generations so accurately that scientists are able to pinpoint what the story related to in the physical changes of the landscape.

Many Aboriginal stories have been dated this way: 7,000 year old memories of volcanoes have come to light, as well as memories of the planting of palms in central Australia over 10,000 years ago, and the memories of sea levels rising 15,000 years ago.

The age of these memories tells us the degree of integrity for truth and justice maintained in Aboriginal communities.

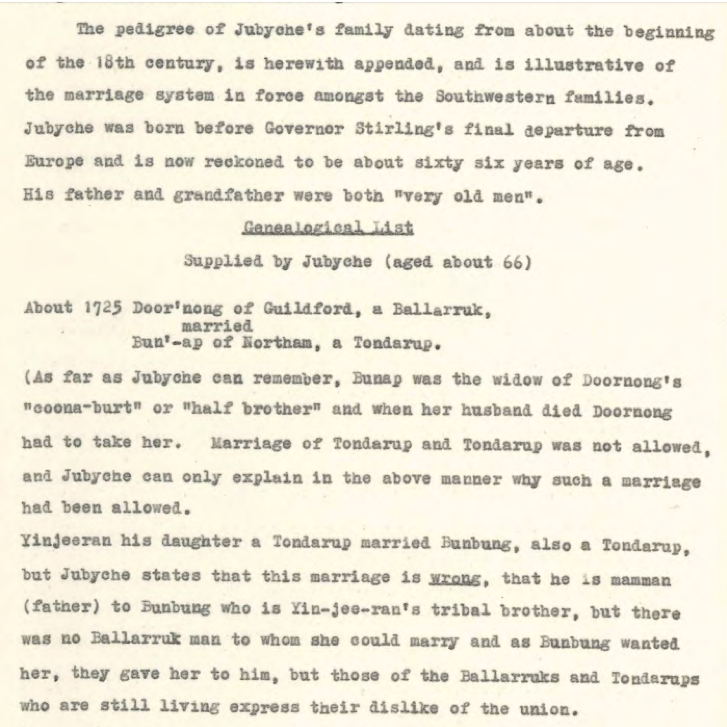

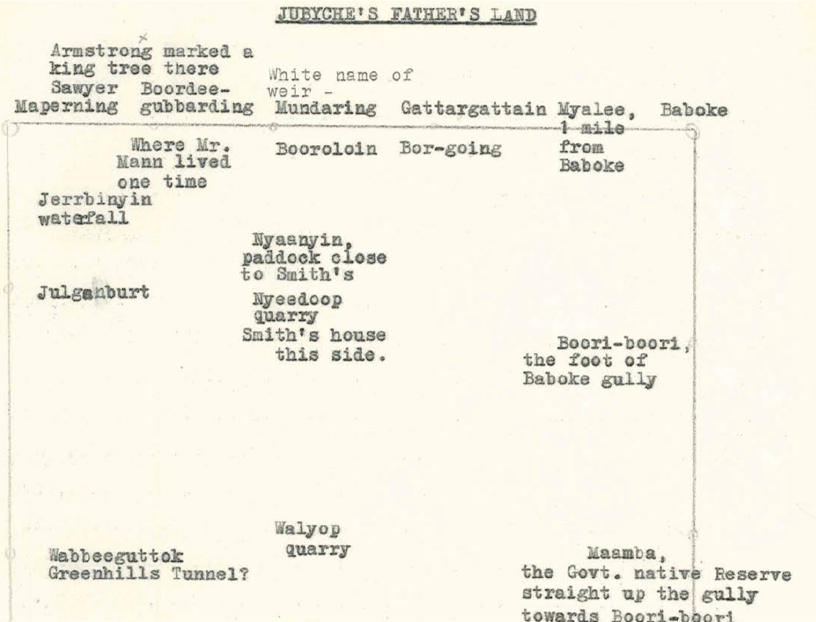

Below is a map of Joobaitch’s land which was passed down from father to son or daughter since time immemorial.

A Noongar critique of whiteness

“disruptr acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the land on which we work, the Wurundjeri, Boonwurrung, Wathaurong, Taungurong and Dja Dja Wurrung people of the Kulin Nation and we pay our respects to their Elders past and present.”

The acknowledgement above denotes Aboriginal land ownership as not real by naming Aboriginal ownership as ‘Traditional’. This is a deliberate obfuscation of what whiteness has done to us and our countries.

A shallow reflection may consider the use of the word ‘traditional’ as normal because in whiteness the more advanced people of British cultures overwhelmed Aboriginal systems of ownership and displaced them as a matter of conquest.

But at the same time, according to the preferred perspective of Australian history, Britain gained Aboriginal people’s countries by terra nullius: an Australian invention to hide the theft of Aboriginal land when Captain Cook failed to follow the Secret Instructions from the British Admiralty to make treaty.

This is whiteness, the constant changing of laws where excuses and justifications are made into law. And this is how psychopathy proliferates in whiteness.

We must all remember what this country looked like before the ravages of colonialism and return this country back to health for the sake of all life on earth.

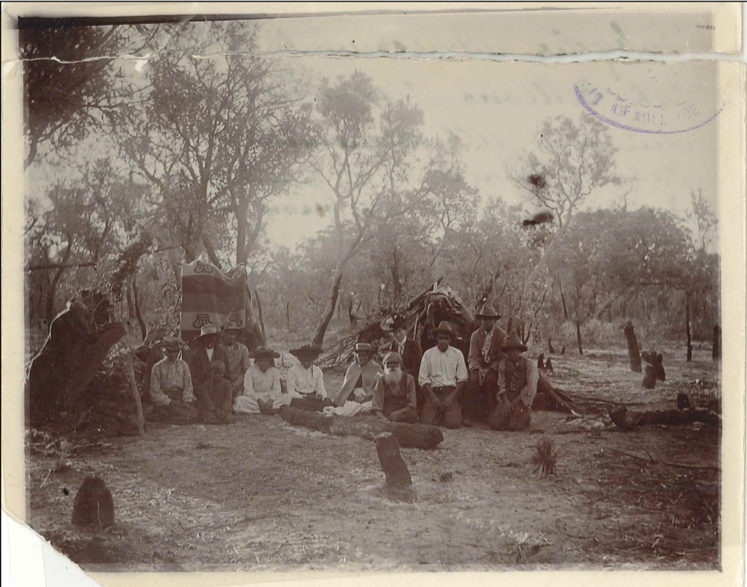

Below is a photo of Joobaitch and his family. His children were not able to stay on their country. They were sent to the Moore River Native Settlement, where most of them died.

Aileen Marwung Walsh is Noongar and Ngalia Anangu. Her research encompasses Aboriginal history from the deep past to the future.

She is currently undertaking a doctorate at ANU and working on a book, to be published by Magabala, about the meanings of personal Aboriginal names and how those Aboriginal names connect people to the life of the planet.

Aileen’s research is deliberately anti-colonial and explores the importance and value of Aboriginal epistemologies.