Families living in high-rise buildings report spending little time inside their homes, instead embracing their local environment on a daily basis and ‘living outside’.

You might have noticed townhouses, apartments and high-rise buildings popping up in your area.

The cultural norm in Australia has been to move into a house when you start a family. But residential preferences are changing, notably for families.

Housing is a key determinant of health, yet high-rise designs aren’t reflecting the needs of their residents.

Dr. Fiona Andrews and Dr. Elyse Warner from Deakin University’s School of Health and Social Development highlight challenges for high-rise dwellers and how to satisfy our changing Australian Dream.

Going vertical

Australia is shifting towards high-density, high-rise living.

“A key reason why more people are living in high-rise apartments is the cost of housing,” Dr. Warner says.

Although we don’t know what will happen due to COVID-19, Dr. Warner says there’s an increase in purchases of new, modern apartments since they cost less than a new family house with land.

“Another reason is location. It may be closer to the city, public amenities, a particular lifestyle, and closer to employment meaning less travel time.

“There’s also an increasing number of women in the workforce. Women may not want to live in the suburbs where long commutes mean less time with children.”

Dr. Andrews says it also reflects our cultural diversity, since many people moving here from overseas are accustomed to high-rise living.

Apartments are largely designed for young professionals or couples, renters, or older couples looking to downsize.

However, the Australian Bureau of Statistics reported that in 2016, almost 44 percent of apartment residents were families with children.

Apartments are often small, with one to two bedrooms, unsuitable for families. Three-bedrooms are usually at the luxury end of the market.

In many apartments, there’s limited internal space and storage. Most have smaller rooms and often no dining room, study or laundry.

Residents may not have all facilities and space required.

While apartment complexes often have communal areas, Dr. Warner says that they’re not necessarily safe or suitable for families and children to play in.

For children, accidents around the home are a common cause of injury.

Dr. Andrews highlights the safety issues for children in the current stock of apartments such as windows, balconies and car drop-off areas.

Apartments may not be adequately sound-proofed, leading to noise disruptions when living close to noisy neighbours.

Children are not easy to predict or control, so parents may have to be ultra-conscious of children’s noise levels, potentially restricting play.

Social life and wellbeing

Opportunities for social interaction and connection can be difficult given the unique designs of apartment buildings.

“Because people are living in close proximity, there’s this idea of maintaining privacy and not overstepping boundaries,” Dr. Warner says. “Residents might not reach out and connect with others.”

Since there are many renters in apartment complexes, Dr. Warner says the high turnover of residents means they might just get to know someone before they move out again.

Neighbours may also not have much in common. For example, families living next to young single renters are in different life stages and less likely to mix.

Limited apartment space, limited visitor parking or high cost of street parking, particularly in city areas, means it’s difficult to have family and friends over to socialise.

Dr. Warner says that a lack of long-lasting social connections can impact social health and wellbeing.

Social connections reduce feelings of loneliness, increase self-esteem and quality of life. Social support is particularly important during the early years of parenting.

“Issues around space and noise means parents may feel reluctant to have gatherings or their children’s friends over for playdates.”

Dr. Warner says that parents can feel guilty that their children are missing out or that they can’t reciprocate social invitations.

“Feelings of guilt amongst parents ties in with their own mental health and wellbeing as well.”

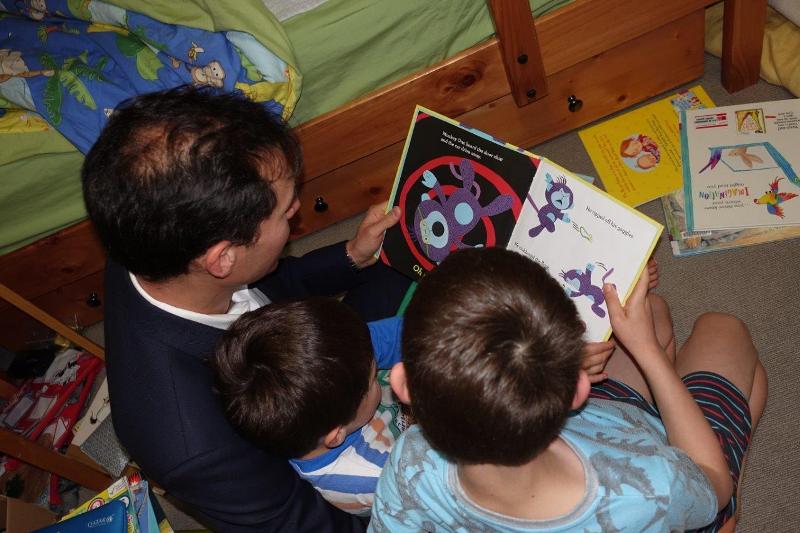

Without much space and socialisation at home, many apartment-dwellers rely on their neighbourhoods to live and build connections.

“Having access to green and natural spaces is absolutely crucial,” Dr. Andrews says. “These spaces support children as spaces to play, learn, take risks and engage with the natural world.”

Houses with backyards are multipurpose: for entertaining, exercise, sleep and leisure.

For those who live skyward, ‘living outside’ – making use of their streetscapes and neighbourhoods – is essential.

They can meet friends at a local café, exercise using outdoor equipment, or organise playdates for their children at the park nearby.

Dr. Andrews says places like the Yarra River, Collingwood Children’s Farm or farmers’ markets are important in areas where there are a lot of high-rise developments.

“Families in our studies said they couldn’t stay in their apartments if they didn’t have access to these things.”

Changing designs and attitudes

Apartment living will continue to play a big part in Australia’s housing future. High-rise homes must be functionable and desirable to live in for all.

Dr. Andrews says families want to be recognised as legitimate residents of high-rise housing.

Developers need to provide a diversity of high-rise housing types, communal areas and parking space that reflects the needs of all.

Dr. Andrews and Dr. Warner are currently working on a project with the Victorian government on family friendly apartments.

Dr. Andrews says that in areas with high-rise housing, local governments need to provide and maintain more safe, clean, high-quality and family-friendly infrastructure and all-weather outdoor spaces like parks, barbeque areas and playgrounds for people to linger.

Accessibility via public transport and traffic calming measures like reduced speed limits are also important.

High-rise homes must be functionable and desirable to live in for all.