Poetry has made a comeback. The rise of Instapoets and Twitter bots have given poetry a cool rep again, but we shouldn’t stop just there.

Even the thought of reading a line of poetry can be intimidating for some.

Often we just need a nudge to explore and the knowledge that a poet doesn’t always write about grandiose depictions of love and death.

Sometimes, they even write about driving home or post-election anxiety.

Claudia Rankine’s ‘Cornel West makes the point…’ shows how traditional poetry forms are being reshaped and transformed with the quotidian.

She writes, “After the initial presidential election results come in, I stop watching the news. I want to continue watching, charting, and discussing the counts, the recounts, the hand counts, but I cannot. I lose hope”.

Many of her poems appear on the page as a paragraph; poetry as a disguised ‘thing’, arguably comforting readers rather than confronting them with a daunting line break.

It drifts away from ideas of lineation, meter, and traditional form to become something more familiar; prose.

Associate Professor Cassandra Atherton, a poet and specialist in the prose poetry genre in Deakin University’s School of Communication and Creative Arts says that poetry is present throughout our lifespan.

Often starting in childhood, gifting us with the ability to memorise and internalise poems. Allowing poetry to expand further than the page and create spaces in our own lives, even small ones.

As A/Prof Atherton says, “we have a living library of poems inside ourselves that we can draw on – that our heart learns something from”.

Prose poetry; entering into something familiar

Many of us are exposed to the poetic word through tedious and often rigorous VCE testing which asks you to look at the body of the poem and peel back its meaning.

However, it can be difficult when the form feels so foreign and perhaps even elitist. A/Prof. Atherton suggests that this may be because the reader hasn’t found the type of poetry that clicks yet.

She says, “sometimes white space or blank space of a line break on a computer screen can create anxiety.”

As a result, she encourages us to return to a visual trickster in prose poetry, she reassures us that this form, “isn’t lineated, it has a sense of onrushing momentum as sentences come one after another and wrap at the right margin, not leaving too much time to think between sentences.”

Readers may feel more inclined to pick up a book of poetry that lends itself to the prose form, while still distinctly acting as poetry. It lulls us into a sense of ‘knowing’, advocating that poetry may not be as intimidating as it appears.

Although it may not be as easy to read as prose, it is a springboard into poetry.

Instapoetry and the urgency to understand

We have to turn and clap our hands in thanks to the Instapoets despite cries that it fails to actually adhere to poetic form. Their platforms have created new audiences for poetry: younger and older, but, overwhelming all more engaged.

In transforming poetry and adding a multi-media element, traditional poetry has been reborn and translated for the modern age.

Despite this, A/Prof Atherton asks us to consider while poetry has risen in popularity again if it has come at a cost of quality.

“I’m really conflicted about Instapoetry. For me, it’s not really poetry. It’s kind of epigrams and short prose about universal feelings – about feeling lonely, or scared or unloved. It explores these notions in clichés rather than in memorable metaphors or conceits.”

“I’d like to think of it as a gateway drug – that people who read Instapoetry (and there are millions who do) would then turn to other forms of poetry. Potentially, this would be wonderful in encouraging a new generation and readership of poetry.”

To establish a greater readership from Instapoetry would be a monumental outcome, as many contemporary Australian poets hope people will engage with their work as well.

Perhaps, though not in the same way, as there is the danger that people who “read Instapoetry without having read other forms of poetry may have expectations about poetry that will be entirely skewed.

Instapoetry works in different ways to most other forms of poetry and doesn’t require multiple readings or encourage the reader to enter the poem in its gaps and spaces.”

“It’s more like a Hallmark card, it makes you feel good because you recognize the sentiment, but there’s not a lot of depth.”

What is the ‘right’ interpretation?

It seems that questions of interpretation are challenged with poetry; our ideas of ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ are destabilised by the implied deeper meaning that poetry invites.

But here is where readership begins to wane, as they encounter the difficulties in reading, suggesting that “poetry shouldn’t be read in the same way as prose”.

A/Prof Atherton suggests that in order to grapple with poetry, we should take our time with it.

She proposes “that understanding one line of poetry should take as long as understanding a paragraph of prose; you can’t read a poem, once, quickly, and expect to comprehend it all – that’s actually part of the joy of reading a poem.”

Even after you have sat curled up in bed flicking back between pages for hours, still bewildered, A/Prof. Atherton encourages us not to lose hope.

“Poetry is often considered difficult because people think there is one monolithic answer in the poem and it’s somehow a test to see if the reader and work this out. But there’s never any one right interpretation”

“I don’t believe even the poet has all the answers as so much in writing is unconscious. I think, when a poem enters the public space, it empowers the reader to bring their own thoughts and experiences to the interpretation of a poem and so the response is always going to be nuanced and differently inflected.”

Taking the leap

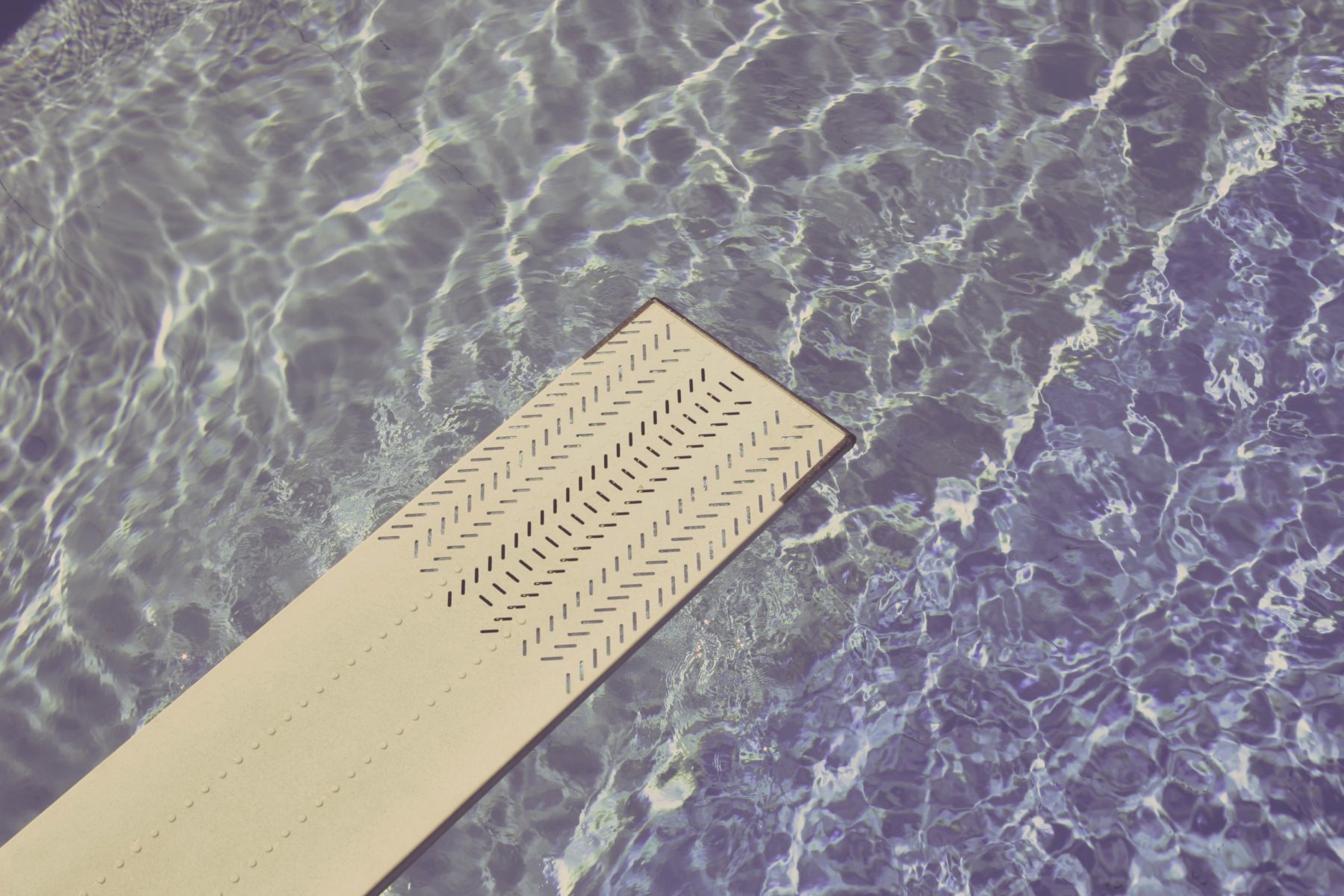

If then, interpretations are subjective and poetry can be more than a profession of undying love or a jumble of line breaks, it can be inviting and even, interesting.

However, it isn’t ‘easy’, in that it requires effort and time to find your own meaning and perhaps that is what is preventing us from reading it.

A/Prof. Atherton agrees the process can be a daunting as if “the end of each line is a bit like being on the edge of the diving board and leaping into space.

It’s often a leap of faith and so it’s a huge achievement just to take that leap— but it’s amazing to find that the beginning of the next line often supports the leap and acts as a kind of buoy.”

“You just have to trust the poem will support you as you read it, by reaching out and guiding you through”.

While digital-based poetry can be accessible for many, we should still extend our comfort zones. Even if it is walking picking up a poetry collection and reading one line, you have taken the first step and now you can continue to explore the waters.