Frequently we think history is incapable of making an impact on our lives now; a distant experience lived by our injudicious ancestors. We are wrong.

The landing of the First Fleet in 1788, for instance, is still so immediate in understanding our nation, with many able to recall the bicentennial and the Australian dream it questionably amplified.

The proximity of this event and many others allows history to wrap itself around the present.

A reassuring hand on the shoulder of not only protesters and policymakers, but around our family dinner tables when the afternoon light has gone and it isn’t socially acceptable to go home.

In these moments, we chat about the past and our shared communities recall their childhoods. Offering up an authentic, tangible platform to question our histories, how they are commemorated and what is widely unknown about our pasts.

It is important that these spaces, now more than ever, extend further than dinner conversations into classrooms and beyond.

Interested to learn more about the past, we asked three of our Deakin University researchers to share frequently little-known histories to hint at the complexities that not all textbooks cover.

Navigating the Indigenous archives

Non-Indigenous histories have frequently dominated the historical record, making it difficult to access Indigenous pasts, however, this doesn’t mean they didn’t happen.

Deakin Senior Lecturer Dr Joanna Cruickshank and her team have been working collaboratively with Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers, community members, creatives and others to create more conversation about the 1881 Victorian Parliamentary Coranderrk Inquiry through the Minutes of Evidence project.

The Coranderrk Reserve was established in 1863, on Wurundjeri country, near what is now referred to as Healesville. It was initially an effective alliance to reserve a portion of their land as an Aboriginal ‘station’ and its growing community established a profitable hops farm.

Although, this success made it an ideal site for settler exploitation.

Dr Cruickshank explains, “these events came to a head in 1881, when the Victorian Legislative Assembly held an Inquiry into the management of Coranderrk.

“Many of the Aboriginal people from Coranderrk testified at the Inquiry, which resulted in widespread public censure of the Board for Protection of the Aborigines and the decision to keep Coranderrk open.”

“Unfortunately, shortly afterwards, the Board effectively lobbied for Parliament to pass legislation that forced all Aboriginal people of mixed descent – which included most of the younger generation at Coranderrk – off the reserves.”

As these events didn’t reflect well on the colonial government, histories like Coranderrk (because there are many other events like it) are often suppressed.

Additionally, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island people have been consistently excluded from “the opportunity of telling their history to non-Indigenous Australians,” meaning we should read and listen beyond official settler records.

While written records (like the minutes of the Coranderrk Inquiry) “don’t give us the whole picture,” Dr Cruickshank says, “they are important nonetheless, particularly when some non-Indigenous people believe that written records are the only reliable source for historical knowledge.”

Becoming a collaborative process that invites us to listen to and read about the past to understand what occurred.

“For me, as a historian, I have had to think much more deeply about who tells our histories.”

Dr Cruickshank reflects on her experiences in the history field and her role as a Chief Investigator in the Minutes of Evidence project noting these experiences made her “very aware that the true history of this place cannot be told without giving priority to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voices and perspectives.”

Beyond Kokoda

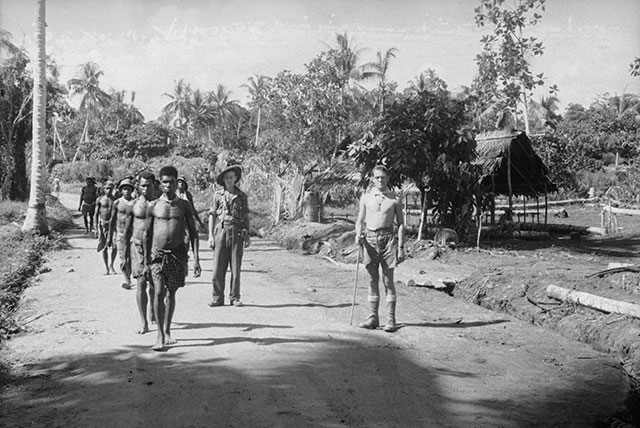

As a lecturer in Papua New Guinean histories and Senior Lecturer in Deakin’s School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Dr Jonathan Ritchie is accustomed to the odd question about the Kokoda track and its associated events.

Dr Ritchie notes that while the Kokoda campaign is undoubtedly important, we shouldn’t stop there. It is also important to acknowledge other violent battles like Milne Bay, Buna-Gona and others, as well as listening to Papua New Guinean voices reflecting on the past.

Dr Ritchie’s involvement in the Australian government-funded project, Voices from the War, produced an online oral history repository devoted to Papua New Guinea (PNG) experiences of WW2.

He notes that making these histories known is important to Australia, although, he would argue, if not more important to Papua New Guinea.

“Focusing on the Papua New Guinea experience of some point of their history whether it’s the war or their independence, really has a great way to give Papua New Guineans agency over their own identity, their own destiny.”

Through clever initiatives like the use of ‘Library Box’, those without access to Wi-fi are able to listen to the stories of the past by utilising the technology of today. Here, the Papua New Guinean people can begin to hear their own national narrative which is sometimes lost in ideas of Australian mateship and bravery.

“Rather than being seen as victims or objects of actions that are being done by others, there is a very strong sense that they are actually agents of their own, they have the ability to control their own futures.”

Dr Ritchie emphasises that, “in Australia, we do have national narratives and we may disagree about what they are but we all have a story we can talk about. More broadly across the colonised world, but certainly in Papua New Guinea, that national narrative is hard to find”.

Realising these histories through oral forms opens up a space for community and ideas of a shared past to develop for not only us but most importantly, the Papua New Guinean people.

What’s the Anzac legend

“Prior to the 1990s, politicians really had a back seat in terms of Anzac commemoration—the returned soldiers themselves ran things,” says ARC DECRA Research Fellow, Dr Carolyn Holbrook from Deakin’s Faculty of Arts and Education.

“Younger people take the political leadership of Anzac commemoration for granted, but people who were around in the seventies and eighties know that things were not always this way.”

Dr Holbrook says that political interest and film representations like Gallipoli have given us a chance to immerse ourselves in the Anzac legend once again.

However, we often don’t realise the relationship between political manipulation and the Anzac narrative.

“Why does the government see fit to spend such massive amounts of money on Anzac commemoration when the budget is so tight in other areas?

“We need to ask ourselves how we are being manipulated and why,” she says.

Many consider their knowledge of Gallipoli and the Anzacs who fought there as pretty clear. After all, we can tell you about our youthful fighters, two-up traditions and of course, Simpson and his donkey.

However, Dr Holbrook affirms that thinking deeply about the past and its political context is vital.

Although some people attach jingoistic and even racist meanings to Anzac, Dr Holbrook says, “It is way too simplistic to badge everyone who feels a strong connection to the Anzac legend in this light.”

“Scholars have shown there are a whole bunch of reasons why people feel attached to the Anzac tradition; family connections are the primary one.

“But sometimes, in the throes of partisan debate, we find it difficult to see the subtleties.

“As good citizens of a democracy, we should always question and be cynical…You can’t tell people what to think, but if you just open their eyes to the history of Anzac commemoration and present them with some historical context, they are perfectly capable of making up their own minds.”

Tuning in to the past

The central aim of history is to learn about what happened before us. It remains impossible to ‘know it all’, but the teachings of our researchers help to show the wide breadth of Australian-focused histories that exist if we wish to explore them.

So, if we are eager to question how valid stories about our teenagerdom are or if that rip-roaring overtold family tale actually happened, maybe we should also start looking for broader histories that got misplaced from those dinner table stories.

Here, we can begin to lean into the echo chamber of voices waiting to share all their different, expansive histories of the world – and perhaps challenge what we accept as the past.