Some of the world’s oldest films are fading into obscurity.

When we talk about ‘old films’, what springs to mind? Perhaps a snippet from something colourful and 1950s, like Singin’ in the Rain, or maybe a silent film featuring a deadpan Buster Keaton?

Cinema, as we understand it today, can be traced back as far as the 1880s.

But films from this period are not known or familiar to us.

Dr Victoria Duckett, from Deakin University’s School of Arts and Education, says that while early works from the silent period of film are screened at some globally significant film festivals, in Australia they are rarely studied at universities and are difficult to access locally.

And early film’s role as an instigator of global media industries is being forgotten in the process.

Fragments and cinémathèques

Many early films have not been fully restored.

Instead, there are fragments. Dr Duckett says that restoring a film is a time-consuming process, beginning with the ability to recognise which film and period of time the fragment is from.

“It requires major experts, people with the visual skills to be able to identify early footage, and months of work,” she says.

“You’re working with history to figure out what you’re seeing.”

Dr Duckett specialises in early French film, from the 1890s up until pre-World War I. This was a period in which France dominated the world’s film industry and was at the forefront of artistic change.

She works within a field of global cultural significance, but the research often doesn’t trickle beyond curious academics.

“It’s a massive area with a lot of archivists and a lot of experts,” she says.

“But surprisingly little is known by the general public about it. They think that the 1960s is old.”

Early films are often overlooked in favour of new releases or ‘classic’ works with well-known performers.

Despite the fact that archives and cinémathèques provide screenings of rare films in their original format, they may not be utilised by the masses in the same way that commercial cinemas are.

“The films might have been sitting in an archive, but no one has seen them for maybe a hundred years, because there are so many,” Dr Duckett says.

“You need interest and forums to show them.”

But early films still have their avenues of appreciation; retrospective film festivals, such as the Italian silent film festival, Le Giornate del Cinema Muto, are places where archivists, scholars, and enthusiasts can view early films from all over the world.

It is also an opportunity for fragments of films to be screened.

Screening these fragments can also help to rewrite the history of cinema as we understand it.

Works may be showcased that feature significant members of the industry who have been excluded, such as female directors and performers, allowing them to be brought back into the public eye.

“Often we look at the history of film in relation to the director,” Dr Duckett says.

“The canon’s been written that most of them are men, but this is not the case in early film. There was the argument made that because film shows emotions, women should be the directors.”

This year, for Le Giornate del Cinema Muto, Dr Duckett has coordinated a programme with Professor Richard Abel, a leading expert in early film from the University of Michigan.

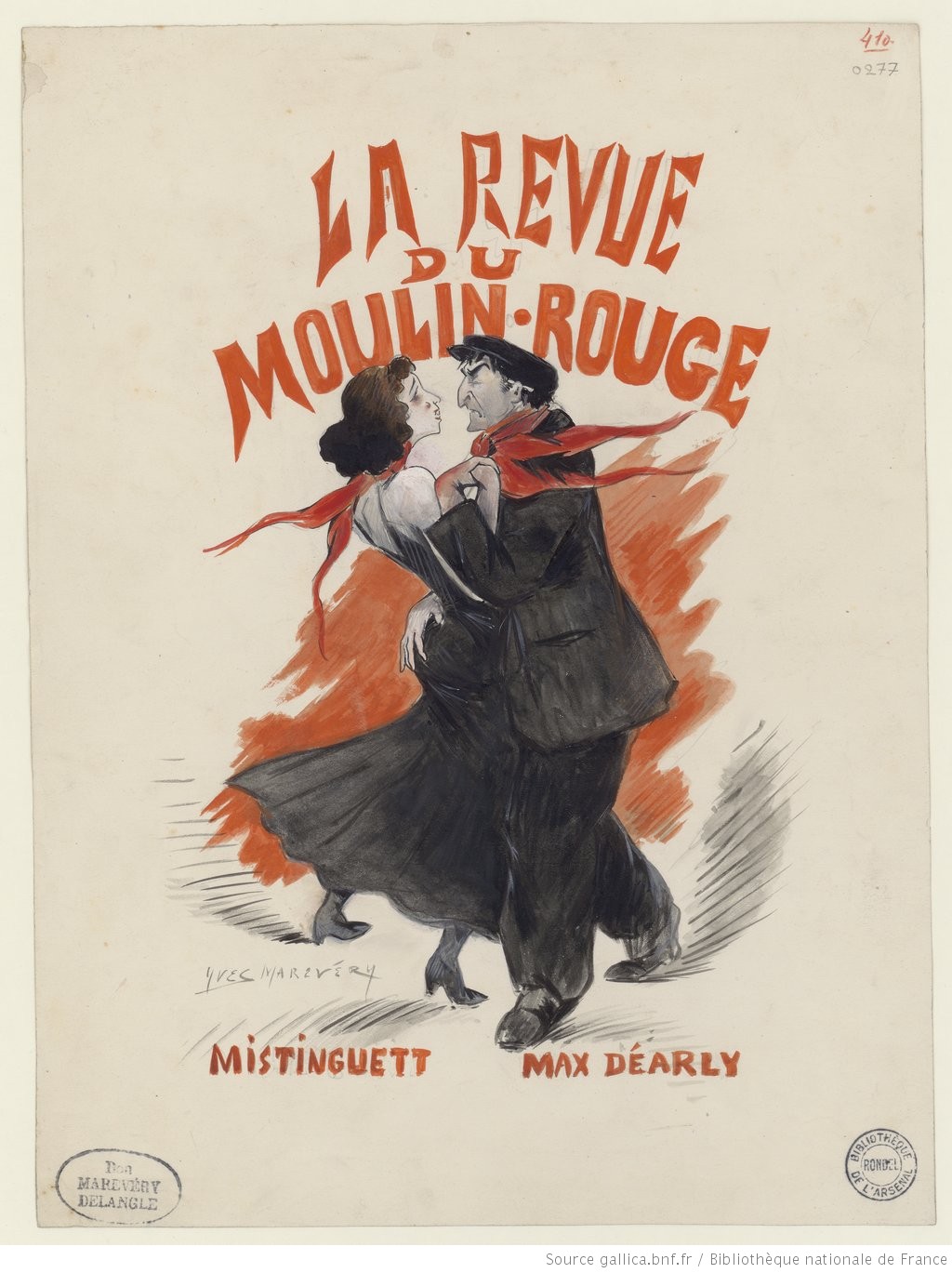

The programme showcases the works of 19th century French actress, Mistinguett, who was once the highest-paid female entertainer in the world.

The works being screened are reconstructed films that France’s leading film archive, the Centre National du Cinéma, and the Eye Film Museum of Amsterdam have granted permission to be used.

“This is probably the first time ever since she died in 1956 that a program is committed to her early film works,” Dr Duckett says. “And we still don’t have all the films.”

Retrospective research

Fragments of historical works are not only important as cultural artefacts, but they can also have a further impact on research.

In screening them, audience members may be able to identify other people in the film that were previously overlooked.

They may also be able to provide answers to other questions about the film the fragment comes from: who was the production company behind it? Where did they shoot it? How was everyone paid?

“To see a fragment of a film, you realise how much is lost and how much we don’t know,” Dr Duckett says.

“It’s about identifying histories within film. We need to identify the performers because in the early period they were really important.”

Many of these early performers had significant careers outside of film, in professional theatre.

Dr Duckett’s research also examines the integration of film and theatre, where famous stage actors and actresses began to enter the film industry in the late nineteenth century, significantly changing and impacting it.

She says that this integrated history of stage and screen calls for a more thoughtful interpretation.

“These films brought with them a changed way of performing,” she says. “If you’re looking at a theatrical star, you’re looking at how they thought of the new medium of film and what they brought to it.”

Dr Duckett says that these performers weren’t abandoning one art form in favour of another. Rather, they were harnessing the power of this new tool to further the reach of their craft.

“These performers sold film through their celebrity, which made them central to the emergence of global media and recognisable far away, in places like Australia,” Dr Duckett says.

“Film was just one extra thing they did. It wasn’t what they were aiming to become.”

For these performers, participating in film was akin to having their photographs taken, so that would be recognised by mass audiences when they arrived in places like America or Australia.

In making themselves available on film, stage actors helped to grow the film industry to have the cultural importance that it does today, as people began to attend cinemas more frequently in order to see these celebrities at work.

Are women being erased from film history, again?

Dr Duckett says that women were a particular driving force for the early film industry’s rapid growth and success.

“Stage actresses were strategic business women,” she says. “More than a hundred years ago, the global entertainment media industry was massive.”

“Women were driving it through their celebrity, by ensuring that they got their work onto film and reaching a mass audience.”

But there is a very real danger of women being written out of film history once again.

Dr Duckett says that it’s imperative that we continue to restore, recognise and archive so that we have a productive retrospective to learn from.

“We’ve got a history of achievement that needs to be acknowledged and taught to future generations,” she says.

“What’s going to happen in the next generation? Are people going to look back and ask if there really was a female presence?”

“I can’t believe it’s taken over a hundred years for people to start talking about women in early film.

“It’s relatively new but it’s exciting and hopefully means that things are changing, not just within individual film cultures, but more generally too.”