An explorative link could help us understand the role of stories in shaping selfhoods, place, and positive futures. It also might be helpful for climate change responses.

When literature meets COVID-19

In a world of social distancing, ransacked shopping centres and lockdown restrictions, we aren’t strangers to apocalyptic scenes.

With radically shifting social and economic systems, some have highlighted the intertwined fates of climate change and the COVID-19 response.

Generally speaking, books have provided integral guidance in this pandemic period.

With reading time on our hands, we set out to understand the purpose of the stories we tell in relation to ‘the end of the world’ and their ability to change us.

Associate Head of Deakin University’s School of Communication and Creative Arts (Research), Associate Professor Emily Potter has always been interested in stories about places and cities, and how we can shape or inhabit them.

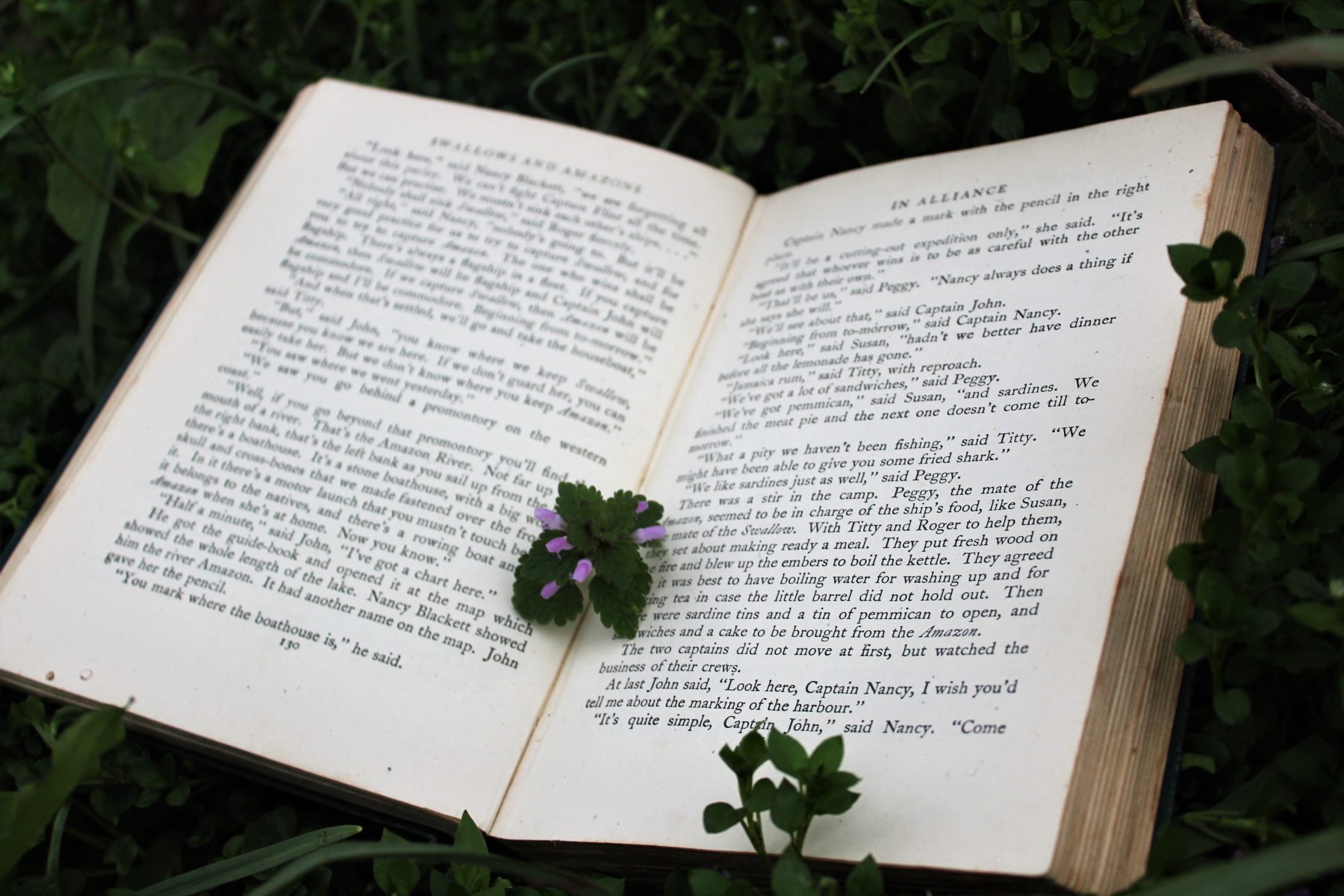

Often, it’s impossible to separate place from a work of literature.

“Literature represents place: it conveys it, depicts it, and can imaginatively transport us to places.”

A/Prof Potter’s journal article ‘Contesting imaginaries in the Australian city: urban planning, public storytelling and the implications for climate change’, has just been published.

Here, A/Prof Potter considers how colonisation, social exclusion, climate change, stories, and cities come together in the making of our everyday spaces in narrative practice.

Although not specifically research on COVID-19, it is still relevant to consider how these themes transcend across the two experiences.

“How we narrate places, through literary texts, as well as through other means, informs how we see, think about, construct, and inhabit these places. And this goes on, regardless, in the face of COVID-19.

“What COVID-19 might do is introduce some alternative spatial imaginaries into literature: if we begin to think about our places as inhabited distantly, this will inform how we make them, in terms of the potential for proximity and distance between people.

“Maybe we need texts that encourage physical distance but emphasise other forms of connectivity, through emotion, dialogue, and shared experience.”

Thinking collectively

Even now, our communities have found new ways to collectively make a positive impact.

These rapid changes, precipitated by COVID-19 have created an environment where working together to wash our hands, keep our distance and become COVID-free is essential.

It seems there is much more we can learn from this community-focused way of thinking than we realise. Even in our approach to climate change, A/Prof Potter says.

“Cultural and literary theorists argue we need to imagine and understand ourselves (be that in literature or other cultural contexts) as deeply entangled with other lives, both human and non-human, and in no way singular or apart.”

Through this lens of thought, we can begin to see how these deeper bonds encouraged by challenges, like COVID-19 and climate change, allow for people to create significant change.

From community-wide hunts for rainbows in house windows to working with colleagues, we are leaning on one another at a distance to make a difference.

“This accords with an ethos of climate activism in which we need collective, public and structural response, rather than privatised, individualised action,” A/Prof Potter notes.

“This is not to deny difference, but to refuse the elevation of the individual, so often associated with hero-ist, human-centred and hierarchal narratives that privilege genders, races, classes or species.”

Inside the narrative

But what does good climate change literature look like?

A/Prof Potter explains that these stories often use experimentation with different forms and techniques that force us (humans) to see ourselves in new ways and challenge existing structures.

By reading a work of climate change literature, many can undergo a kind of linguistic learning where ideas, concepts and understandings can be re-shaped.

The act of picking up a book and listening to its messages can even work to affect positive change as new voices are heard.

“Some of the most powerful of these works, in an Australian context, are by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, who refuse western frameworks and instead write out of Indigenous ways of thinking and knowing.”

A few notable works include How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World by Deakin University academic Dr Tyson Yunkaporta, Bruce Pascoe’s Salt, Alison Whittaker’s Blakwork and Alexis Wright’s The Swan Book among many others.

“It is through narratives such as these, which refuse and overthrow the inherited frameworks that are complicit in climate change, that different, positive futures can be glimpsed,” A/Prof Potter says.