Can you imagine a future where a robot or other autonomous system works beside you, knowing you so well it can suggest the best product for your needs?

Or a robot that offers you advice on tricky day-to-day problems – like step-by-step instructions as you assemble your new interactive personalised computer desk – and could even drive your car for you?

This future is just a hairsbreadth away, and excites and frightens most of us in equal measure.

What about the risks of giving machines autonomy?

Could they harm us?

What about our jobs?

And does this future risk our own resourcefulness, resilience and autonomy?

Bright-eyed and excited to ponder ideas about tomorrow, futurist and AI meister Saeid Nahavandi never runs short of ideas about the future.

But, as one of the world’s most respected artificial intelligence and robotics experts, his vision is much more grounded in what’s possible than most of us.

Saeid works on technologies that we will see ten years from now and will underpin the next era of human/machine interaction.

He works with global aerospace giants like Lockheed Martin and Boeing, defence departments in Australia and the US, and many industry, technology and health sector collaborators, including experts from the world’s top universities like Harvard and MIT.

As head of Deakin’s Institute for Intelligent Systems Research and Innovation (IISRI), Professor Nahavandi leads a 100-member research team that’s positively bursting the boundaries of what’s possible with technology.

Their work has led to two major start-ups and tens of millions of dollars in industry research contracts, working on autonomous robots, self-driving vehicles and haptics, amongst a stream of cutting-edge innovations that aim to make life easier, healthier, safer and more productive and exciting.

Saeid agrees our concerns about the future of technology are valid.

Safeguards are needed.

“It’s important we have global dialogue about the risks and ethical consequences of technological advancement across society, from health, to defence, to our everyday lives,” he said.

“Computers will be able to think faster than humans in many situations in the future. There are researchers in the world who try to take humans out of the loop and create autonomous machines that can make their own decisions and take action based on them. “

The fundamental imperative, ethically, is for humans to be on the loop always, at the apex of all decisions, now and into the future. Robots and other types of technology are there to help human ingenuity, capability and creativity – serving the human in real time.

“We need ethics to guide technological development, but we can’t lose sight of the fact that technology offers huge potential for improving peoples’ lives.”

Symbiosis – hand in (robotic) hand

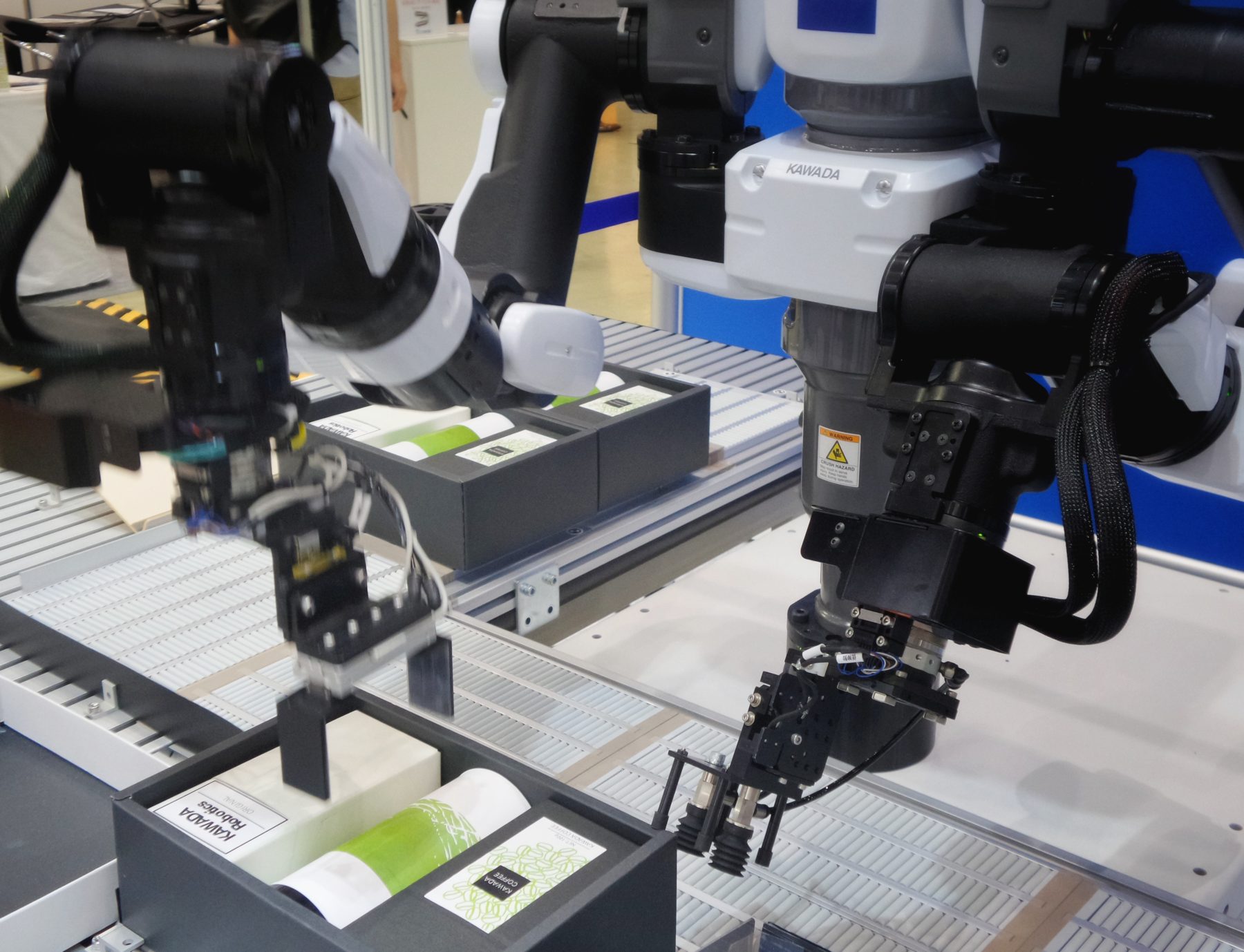

Saeid is certain the next tech era’s signature will be hand-in-hand collaboration between people and robots, and people and autonomous systems (collections of networks all managed by a single entity).

“AI will be part of our life, enhancing its quality in a similar way to today, but it will be much more sophisticated,” he noted.

“Within two decades, humans and robots will have a symbiotic relationship. We will co-exist together.

“In ten years, there will be computer systems that predict your intentions and assist you in performing tasks. While we are seeing that already with Spotify, Netflix or smart phones, it will go much further.

“Your computer will know your routine through analysing patterns of behaviour. It will know your stress levels by monitoring your heart rate and other bio signals.

“As one example of how technology will change the future, at 5pm, your car will know you’re going home and who you’ll want to communicate with using holographic phones.

“It will know your stress levels and set the music, light and temperature to match your mood and perhaps give you a neck and back massage or other therapeutic type of care, while taking you from one place to the next.

“Some of this can be done now.”

Zeroing in on trust

The main challenge for AI developers today concerns allaying human fears about robots.

Fanned by the flames of movies like iRobot and Chappie, not to mention real stories about unsafe autonomous vehicles – and huge transformations in the workforce – these concerns are being voiced by respected thinkers.

The likes of Stephen Hawking and Elon Musk have claimed that AI is a “fundamental risk for civilisation” needing urgent government regulation.

Saeid and his team are confronting this challenge head-on; seeking to understand and build human trust in machines – and the best ways to ensure this trust is well placed.

“A new focus for IISRI is to drill down and identify the elements that will let a person allow a robot be more involved in a medical procedure or be confident to travel in a self-driving car, for instance,” he explained.

“Science is pacing towards an ‘autonomy of things’ faster than society can understand what is meant by ‘autonomous systems’.”

From the broad perspective, the challenge is three-fold:

- a communication challenge, to reassure people about what computers can and can’t do;

- a challenge to ensure technology developers are united and humans remain on the loop;

- and a policy challenge to ensure the regulations are set up to safeguard us.

Working with other world-leading research teams, including Professor Kevin Kelly from the Robotics and Innovation Lab at Trinity College, Dublin, IISRI is seeking ways to measure trust between human and robot, and machine and machine.

The team has identified the key elements of trust: predictability, dependability, assurance (that autonomous systems are not competitors, but allies) and control (humans always have the ability to override control).

The team has devised objective measures of trust in an initial research phase, which can be quantified through physiological responses such as eye movement, heart rate, brain activity, muscle activity, perspiration and breathing.

Once understood, these can be embedded into technological development to “improve the human/robot fit.”

This work has culminated in iTrust Lab, established at Deakin this year, where researchers work with haptic, tele-operated and autonomous-capable robots, as well as measurement devices like EEGs (brain activity), fNIR (functional near infra-red imaging), EMGs (muscle activity) and eye-tracking equipment.

The lab is already working on a multi-million dollar project aimed at refining autonomous vehicles.

Our brain – the perfect AI template

The human brain has been the template for the massive advances made in AI, robotics, autonomous systems and machine learning in the past decade.

“We’re now seeing how we can augment autonomous systems with models of human intentions and behaviours that will allow us to extend applications and improve trustworthiness,” said Saeid.

“For instance, we know that ‘intention aware’ systems that function more like humans are crucial to improving the safety of autonomous vehicles. The non-verbal communications (like eye contact) that take place during driving play an important role in road safety.

“For a computer to understand these and other signals, such as identifying which way a pedestrian is likely to walk or a kangaroo will jump, is extremely challenging.

“We are working on a very sophisticated algorithm that we hope will crack this challenge and accelerate the development of safe autonomous vehicles globally.

“This is a journey we started in 2007 that particularly involved a lot of research on human-machine interface and haptics.

“Now, we’re going a level deeper to see how the brain is functioning, while people interact with a machine through this equipment that will give us a physiological measure, rather than a subjective one.

“We are also discussing with industry partners how we can deduce the quality of learning in a simulation while a task is given, by monitoring brain activity.

“This research is likely to lead to personalised, precision training that adapts to an individual’s brain waves through lightweight, portable EEG or fNIR.

“This system could be used to train airline pilots or surgeons in the first instance, but could eventually be used across society as the technology becomes more affordable and sophisticated.”

The potential of all these innovations is mind-boggling, but Saeid emphasises that, ultimately, it is all about improving life for individuals. Throughout his career – from his PhD in robotics at Durham University, to his eight years at Massey University (NZ), to his 21 years at Deakin – it has been people who have brought him to work each day.

“Every hour of my day I enjoy seeing my colleagues’ faces and working with them,” he said.

“We challenge each other and we wrangle over ideas about the human/machine interface and how we can make machines work better with humans and machines work better with other machines, so we can make a better future.”

He knows his work on technology and trust is just one strategy needed to create a safe high-tech future.

Regulations, laws, responsible governments and continuing debate will also be essential and, ultimately something very human, hope.

Professor Saeid Nahavandi is Director of Deakin’s Institute for Intelligent Systems Research and Innovation and Pro Vice-Chancellor for Defence Technologies.

He chairs two committees of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) – the world’s largest computer/electronics professional association – and co-edits it’s Systems Journal.