Defining a wetland is a difficult task, even for scientists today.

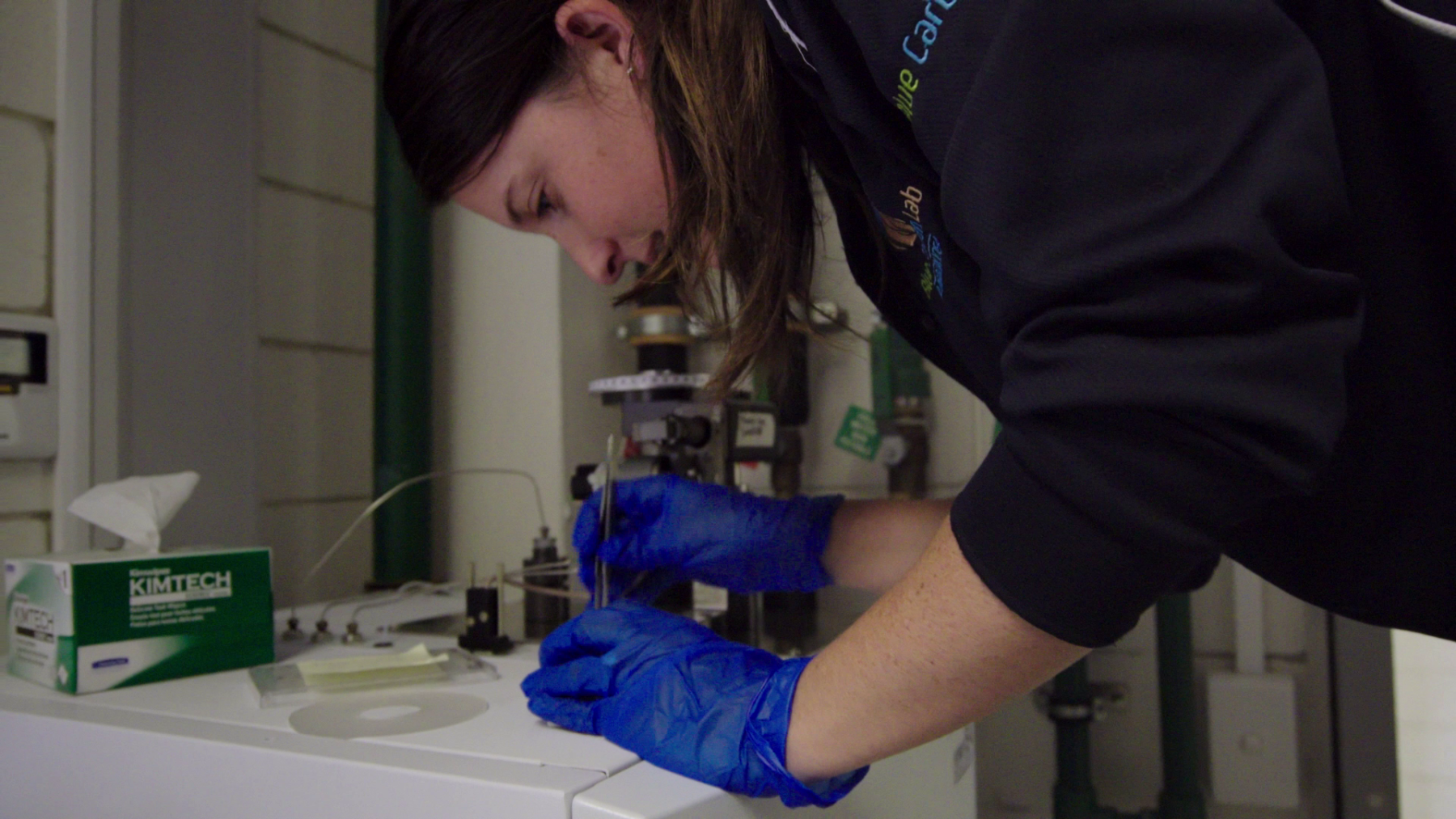

The team at the Blue Carbon Lab does a lot of groundbreaking research in harnessing the powerful ability of coastal vegetated ecosystems to sequester carbon, and thereby help mitigate climate change.

These ecosystems also include the unassuming wetlands of Australia.

disruptr. sits down with lab member, Katy Limpert, to discuss what really makes a wetland so unique.

How is a wetland ecosystem defined?

Although there is still some debate on the definition of a wetland ecosystem, government agencies, such as the US. Fish and Wildlife service, defines a wetland by having the following attributes:

1) Dominated by hydrophytes (vegetation that thrives in or on water)

2) A soil profile that has water above or below the surface

3) Water is present in the ecosystem during the growing season

Similarly, the Department of the Environment and Energy define wetlands as the following:

· bogs, fens, and peatlands.

· swamps, marshes

· billabongs, lakes, lagoons

· salt marshes, mudflats

· mangroves, coral reefs

Part of the difficulty in defining a wetland is the high variability of these ecosystems due to their differences in size, soils, climate, water level, biogeochemistry, vegetation type, and anthropogenic disturbances.

What makes it unique?

A wetland ecosystem is the “best of both worlds”, essentially the transitional zone between terrestrial and aquatic systems.

Wetlands provide vital ecosystem services such as the cycling of water and nutrients, and providing habitat for a variety of flora and fauna.

Wetlands are also unique due to their ability to hold large amounts of carbon by sequestering 30% of all soil carbon globally. Wetlands take up carbon during photosynthesis and bury undecomposed plant litter in anaerobic soils.

Freshwater and coastal wetlands sequester 34-50% more carbon than terrestrial forest ecosystems.

The water regime of a wetland determines the soil, plant, animal, and bacterial communities of the ecosystem; often favouring hydrophilic species. Thus, wetlands are an important feature of the landscape.

Why are wetlands so important to the wider ecosystem?

The ability of a wetland ecosystem to store water, filter pollutants and cycle nutrients creates an ecosystem that is essential for the well-being of the planet.

Wetlands act as a flooding buffer by holding excess water at the surface and in groundwater reserves. Coastal wetlands, for example, reduce the severity of storm surges by lowering wave height and wind speeds before they reach land.

During drier conditions, wetlands act like a sponge by retaining water while other ecosystems are dry. The arid regions of Australia depend on deep, freshwater marshes to retain water in pools during long periods of drought.

Wetlands also capture sediment and other particulates as water moves over the land. Soil and water overflow is slowed when the water in a wetland moves around wetland vegetation and eventually retained by the soil.

Fertilisers, manure and sewage that enters these ecosystems are often dissolved by water, broken down by microorganisms and absorbed by plant roots.

Through this wetland filtration process, pollutants are often removed from the water by the time it leaves the ecosystem. T

he higher water and nutrient content of these ecosystems generally increases vegetative growth which further promotes habitat for fish, reptiles, birds, and invertebrates.

What kind of species depend on wetlands?

Wetlands across the globe support a variety of plants (trees, shrubs, and other hydrophytes) and animal species (mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles, fish, and many invertebrates).

These plants and animals depend on wetland ecosystems for water, nutrients, food, shelter, breeding and nesting sites for part or all of their lives.

River red-gums, an iconic Australian wetland species, offer nesting habitat for countless birds, mammals and invertebrates.

Mangroves around the coastal regions of the world are extremely important wetland vegetation for protecting fish nurseries and rookeries for birds.

Migratory species, such as birds, depend on wetlands as a refuge because they provide food, water, and protection during their long journeys.

What are the consequences when we fail to protect and conserve these wetlands?

Over the past 100 years, over 50% of the world’s wetlands have disappeared leading to severe consequences that threaten the health of humans and wildlife.

As wetland ecosystems disappear, so do their ability to hold water in groundwater reserves, collect sediment, and filter harmful pollutants.

The loss of wetlands has significantly increased flooding in urban and rural areas, leading to an average of 500,000 kg of soil and pollutants washed into catchments globally per year.

A study analysing the economic benefits of wetlands in the United States noted that maintaining 15% of the land area of a watershed in wetlands can reduce flooding peaks by 60%.

An assessment made by the World Bank in 2004 found that preserving ecosystems, such as wetlands in Australia, are seven times more effective than the costs it takes to repair areas destroyed by natural disasters.

Further, loss and degradation of wetland soil have been linked to loss of soil organic carbon that had been previously stored.

For instance, estimated loss of wetlands since European settlement in Victoria has resulted in the emission of 22–74 million mega grams of CO2 from previously sequestered soil carbon.

Increased flooding from wetland loss and land use changes has destroyed agricultural fields, fisheries and food/habitat for wildlife.

The destruction of Australian wetlands further reduces essential habitat for wildlife, impacting commercially important fish and shellfish populations that are valued at $3.06 billion in 2016–17.

What is Citizen Science and how is that helping Blue Carbon Lab?

Citizen scientists are volunteers and public participants that collaborate in various scientific research projects to better understand the issues that we face as a society.

The objective of citizen science programs is to engage the public on scientific issues by allowing the public to gain hands-on expertise from scientists whilst adding to important information in scientific databases.

Several benefits come from a citizen science program including: collaboration between the scientific and public community, learning opportunities, social benefits, publication from the research and overall contribution to improving the planets health and well-being.

Blue Carbon Lab, in partnership with HSBC & Earthwatch, created a program in which local bankers in Sydney, Melbourne, and Auckland participate on projects that identify the processes in which coastal wetlands store carbon.

The information collected during these various projects will be analysed by national and international researchers to better understand carbon dynamics within Blue Carbon ecosystems.