Professor Brett Bryan and other world-class experts from Deakin University’s Centre for Integrative Ecology are calling on us all – from governments to individuals – to take more action to save nature before it’s too late.

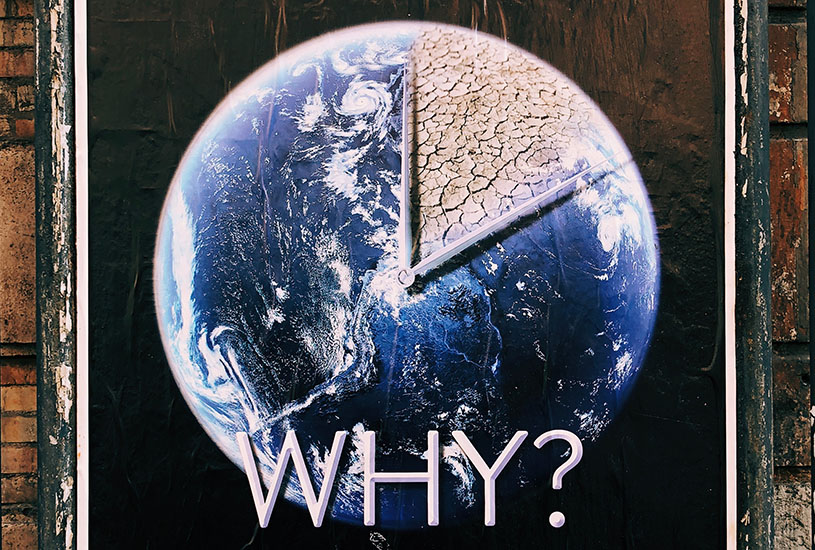

Life on Earth is under siege and its demise is now occurring in plain sight, in disturbing fashion.

Multiple interacting and compounding threats to nature, such as climate change, unsustainable agriculture and fisheries, deforestation, wildlife hunting and poaching, and proliferation of invasive species, are destroying nature, killing-off more and more species, and compromising entire ecosystems.

The pace and scale of change means many species are left with little chance to adapt to change, and are therefore being driven to extinction, as a result of our choices.

The Earth’s sixth mass extinction event is now well under way, and this time it’s our fault.

The perilous state of our natural world made headlines in May following the release of a major inter-governmental report on the decline of biodiversity and ecosystem services worldwide.

No longer is debate about the decline of the natural world limited to academic circles. No longer are its processes cryptic, its outcomes uncertain, or its solutions something we can put off for later.

As scientific understanding and public awareness of the profound impact our actions are having on the natural environment accelerates, so does the urgency to act to mitigate it. Failure to act now poses a significant existential risk for humans as a species.

We are causing the extinction of our life support system, the plants, animals, and other species we share Earth with. With the recent death of the last female Yangtze giant softshell turtle (Rafetus swinhoei), that species will shortly be consigned to museums and memories.

The Bramble Cay melomys (Melomys rubicola: a rat that lived at the northern tip of the Great Barrier Reef) will now be remembered as the first mammal species whose extinction was likely caused primarily by climate change.

In recent years, at least one bat and two lizard species have become extinct on Australia’s Christmas Island, caused by invasive species and a failure of the nation’s environmental bureaucracy.

These are but a few extinctions that we know of. The real number is likely to be much, much higher.

There is also evidence that even some common species are declining, which may destabilise entire ecosystems through loss of species interactions and ecological functions, such as pollination.

House sparrow (Passer domesticus) and starling (Sturnus vulgaris) population declines across Europe are a stark example.

Worldwide, a recent review reported over 40 per cent of insect species are at risk of extinction, primarily due to land-use change and agri-chemical use in agriculture.

In the Luquillo rainforest of Puerto Rico, for example, arthropods (eg: insects, spiders) have declined by 10-60 times since 1970, most likely due to a 2.0 degree climatic warming, causing a knock-on effect for populations of birds, lizards, and frogs that feed on them.

While Insectageddon has been criticized as alarmist, the potential failure of very many important roles played by insects across natural, urban, and agricultural systems, such as the pollination of crops, could be catastrophic for both nature and people.

Fifty-seven years after Rachel Carson published Silent Spring, it’s hard to argue that we weren’t warned.

The potential plight of insects also prompts concern about the condition and trajectory of fungi and microorganisms – the unseen creatures that have substantial roles in the biogeochemical cycling of energy and matter through ecosystems.

Unsustainable agricultural practices (largely based on monocultures and the intensive use of fertilisers and pesticides) not only adversely impact biodiversity, but also jeopardise the health and productivity of land, thus compromising our ability to grow nutritious crops in the future.

Failing to arrest these trends would mean a continuing vicious circle where higher chemical inputs are used to compensate for deteriorating soil nutrient content, which then further degrades biodiversity and soil health, and increases risks for human health.

Ecosystems are crashing

While science has long predicted the crash of entire ecosystems resulting from the effects on their component species, we are now beginning to see this play out in real time.

In Australia’s Darling River the over-extraction of water resources, combined with deep drought, led to widespread anoxic conditions, algal blooms, and a massive fish kill event. Millions of fish died, with some estimated to be decades old, indicating they had lived through the Millennium Drought in the 2000s.

This summer’s climate change-induced wildfires in the Tasmanian temperate rainforests have destroyed 205,000 ha of relict Gondwanan ecosystems, like pencil, King Billy and Huon pine, which have thrived in situ for thousands of years.

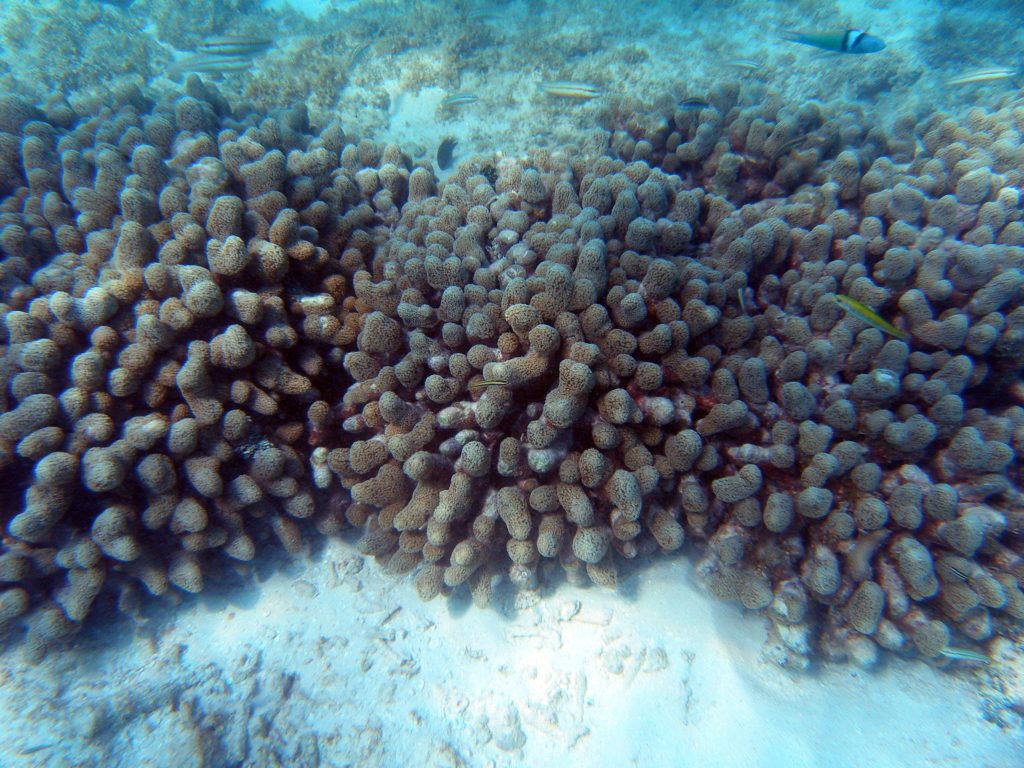

Oceans have faced far fewer species extinctions than on land, but their time may still be coming with the growing blue economy, which is seeing industrialisation of the ocean for energy, food, and transportation.

The repeated mass bleaching events of the Great Barrier Reef are particularly confronting.

Sustained overall increases in ocean temperatures, punctuated by more severe El Niño-induced warming events, are likely to have caused the collapse of large sections of the coral reef ecosystem, and indeed other coral regions globally.

Australia’s unique wet tropics rainforests may be next.

These examples seem to be increasing in frequency and severity. It would be reckless therefore not to consider the very real possibility that we are witnessing the early signs of environmental collapse.

It goes without saying what an unthinkably monumental intrinsic loss this would be, notwithstanding the concomitant loss of ecosystem services — the many benefits people receive from nature — and the disruption of the Earth system.

A precautionary approach dictates acting now, as prevention is far more effective than trying to repair substantial, potential irreversible, damage.

How do we drive change?

We must urgently stop the extinction of species and prevent further ecosystem collapse.

A comprehensive approach is needed, from addressing the key drivers through high-level policy and governance (e.g. decent climate, energy, and land-use policy; eliminate corruption), right down to the role of local communities in promoting robust pathways to sustainable futures.

Individuals, especially in the developed world, can do their bit in driving change by reducing their footprint.

This can include lifestyle changes, which, when scaled up, can make a large overall difference (e.g. having fewer children, eating less beef, buying less stuff, reducing waste and recycling, reducing car and air travel, installing rooftop solar panels, making wise consumer choices, and pressuring governments at all levels to do more).

Science communication is also critically important, as well-told stories about the plight of the natural world and our role in it are essential in helping change the weight of public opinion, which can in turn motivate action by government and business. And society.

Overwhelming evidence of the escalating threat of climate change has motivated activism such as Climate Strike and the Extinction Rebellion.

These global mass movements provide platforms for people around the world to express their desperation at government inaction, and the catastrophic loss of biodiversity and its acceleration under climate change. Evidence-based, on-ground actions, backed up by careful measurement and monitoring across key indicators, are also critically important for making change on the ground.

Turning the perilous trajectory of nature around will require robust actions at all levels to have the best chance of effecting positive change now and into the future.

Initiatives like Half-Earth and the Global Deal for Nature are important examples of tangible, science-led strategies for advancing towards these goals. These movements are essential, but not sufficient.

Our concern is not just for threatened species, but all of nature. We may well be approaching a tipping point, a phase shift into a state of accelerated decline (a biodiversity death spiral) resulting from human impacts, as reflected by the increasing frequency and severity of catastrophic events.

Without a global emergency response, this is likely to accelerate as the causal factors continue unabated and our priorities remain incompatible with the natural world.

There is no question that we will need to throw every ounce of human ingenuity, investment, innovation, and effort at its solution, starting immediately.

We are already very late.

Brett Bryan

Professor of Global Change, Environment and Society

Euan Ritchie

Associate Professor in Wildlife Ecology

Tim Doherty

Research Fellow

Don Driscoll

Professor of Ecology

Michalis Hadjikakou

Research Fellow

Enayat Moallemi

Research Fellow

Peter Macreadie

Associate Professor of Environmental Science