A team of researchers has created a four-step guide for defining ecosystem collapse, to improve resource management and help protect ecosystems.

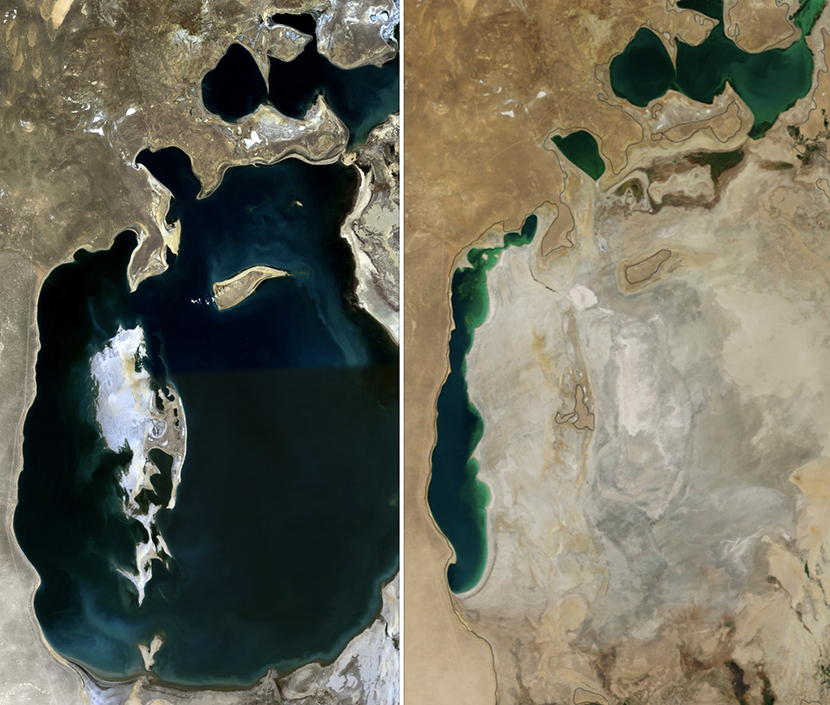

With over 1,100 islands once dotting its waters, the Aral Sea, bordering Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, was one of the four largest lakes in the world. It no longer exists. The water volume has fallen by 92 per cent due to excessive removal of water for irrigation over the past 30 years. The fish, invertebrates, waterbirds and reed beds have vanished, leaving a desert with saline lakes.

Closer to home, the massive, spectacular mountain ash forest stretching across 150,000 hectares of Victoria’s central highlands – from Kinglake to Woods Point – and the vast saltwater lagoon ecosystem in South Australia’s Coorong are both critically endangered ecosystems. The mountain ash ecosystem is threatened by a combination of logging and bushfires, and experts are predicting it will almost certainly collapse in the next 50 years.

With the world facing mass species extinctions due to climate change and over-development, Deakin University researchers and their colleagues from several Australian universities, along with Dr Paul Rodríguez of Venezuelan Institute for Scientific Research, have devised a system to be used globally by ecologists, natural resource managers and government bodies to identify ecosystem collapse – allowing resources to be directed to areas most at risk.

Deakin PhD student Jessica Rowland, an author, with Deakin Research Fellow Dr Lucie Bland and Dr Emily Nicholson, on a paper recently published in “Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution,” said “species are going extinct, ecosystems are collapsing, and these losses are only expected to rise”.

“To measure the risks posed to species and ecosystems, conservation scientists use Red Lists, such as the International Union for the Conservation of Nature Red List of Ecosystems (RLE),” she explained.

The RLE is the global protocol for assessing risk to ecosystems. Risk is measured based on change in ecological indicators through time and across space. Indicators can represent the geographic distribution (where the ecosystems is found), biotic features (living organisms, including plants, animals, fungi) or abiotic environment (non-living things like climate, soil) that characterise the ecosystem.

“To measure these risks, we need to define a clear end point to decline. The endpoint for species or populations is extinction, when all individuals have died; but for ecosystems, defining the endpoint (ie ecosystem collapse) is a little trickier,” Ms Rowland said.

[testimonial_text]As the world is rapidly changing, understanding what risks are posed to ecosystems allows for the most appropriate and timely actions. Ensuring ecosystem collapse is accurately defined will increase our ability to take effective actions to mitigate changes in the future.[/testimonial_text]

[testimonial_picture name=”Ms Jessica Rowland” details=”Deakin University PhD Student”]

[/testimonial_picture]

[/testimonial_picture]Ms Rowland explained that an ecosystem moves into a collapsed state once it has lost its defining biotic or abiotic features or has been replaced by a different type of ecosystem.

“The difference may be stark between the intact, or initial, and collapsed states of an ecosystem, based on change in one or more indicators. Yet it can be challenging to quantitatively define the point at which an ecosystem moves into a collapsed state for each indicator, ie a threshold of collapse,” she said.

To understand how ecosystem collapse has been defined in the past, the researchers examined research in the largest aquatic habitat on Earth, the middle depth of the ocean (marine pelagic) and temperate forest ecosystems around the world. They found that previous studies of marine pelagic ecosystems, for instance, tended to focus on the functioning of the system. These studies typically used indicators of biotic and abiotic features to measure change.

“We found that many studies failed to adequately describe the initial and collapsed states of the ecosystem, or how an ecosystem may change between states – for example, the ecosystem’s biota, abiotic environment, ecological processes and spatial distribution.” Ms Rowland said.

“This means that a lot of details are missing that should be included in assessments so we can have a much more comprehensive picture of our ecosystems, the state they are in, and where they might be headed.”

From the review, the authors identified four steps for defining ecosystem collapse:

(1) Quantitatively define initial and collapsed states

At the outset, the initial and collapsed states of the ecosystem must be described, of which there may be more than one (for example, natural states of eucalypt forest ecosystems include before and after bushfires). This allows researchers to determine whether there have been any changes over time or across the area of the ecosystem.

(2) Describe collapse and recovery transitions

Describe the ways that an ecosystem can move into or out of collapsed states. This can help highlight useful indicators, collapse thresholds for each indicator, and determine whether there are intermediate ecosystem states.

(3) Identify and select indicators

It is pivotal that the right indicators are chosen to represent different aspects of an ecosystem. These indicators need to be informative and sensitive. There may be many ways in which an ecosystem can move towards collapse, so using a range of indicators of the geographic distribution, biotic and abiotic features can improve the chances of detecting change.

(4) Set quantitative thresholds for collapse

Lastly, quantitative thresholds of collapse must be defined for each indicator that provide a meaningful distinction between an intact and collapsed ecosystem. There is often uncertainty in the exact point at which this can occur. To deal with this uncertainty, it is best to include bounded estimates for each threshold.

Read more:

• “Developing a standardised definition of ecosystem collapse for risk assessment” in “Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution.”

Authors: Lucie M Bland, Jessica Rowland, Tracey J. Regan, David A. Keith, Nicholas J. Murray, Rebecca E. Lester, Matt Linn, Jon Paul Rodríguez, Emily Nicholson.

Caption: The Aral Sea before (1985) and after (2011) the ecosystem collapsed

Published by Deakin Research on 25 January 2018