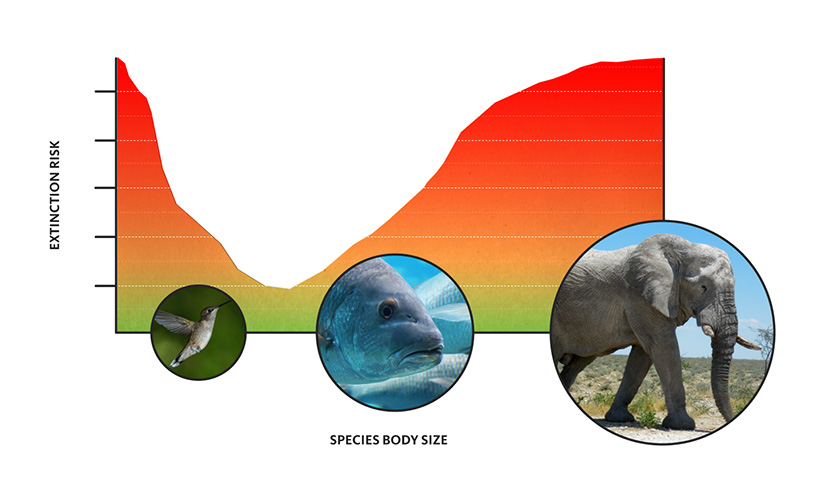

New research has shown that extinction risk is the greatest for the world’s smallest and largest vertebrates, but for very different reasons.

The results of an international study into the relationship between body size and extinction risk have practical implications for animal conservation, according to a Deakin University researcher.

By examining a database of more than 27,000 vertebrates, and analysing the relationship between extinction risk and body mass, the study, published today in “Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,” found that the heaviest vertebrates were most threatened by a rapidly growing population of human meat-eaters.

In contrast, the lightest vertebrates were most in danger from habitat loss and modification resulting from pollution, agricultural cropping and logging.

Among the groups of animals evaluated were birds, reptiles, amphibians, bony fish, cartilaginous fish (mostly sharks and rays), and mammals, with more than 4000 listed as threatened or endangered.

The research was led by Oregon State University in the US and supported by Deakin and the University of Sydney.

Dr Thomas Newsome, a Research Fellow with Deakin and The University of Sydney, said the results put the spotlight on 241 threatened species in Australia.

[testimonial_text]Fifty-five per cent of these species are threatened by biological resource use, which includes hunting, logging, and fishing. As an example, the northern hairy-nosed wombat is one of the rarest land mammals in the world and is critically endangered. A key threat to this species is habitat loss. But Australia stands out in that a high proportion of species are also threatened by invasive species.[/testimonial_text]

[testimonial_picture name=”Dr Thomas Newsome” details=”Centre for Integrative Ecology”]

[/testimonial_picture]

[/testimonial_picture]Dr Newsome, who is an Alfred Deakin Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Deakin’s Centre for Integrative Ecology (CIE) has conducted extensive research into how the behaviour of humans and predators such as foxes, wolves and dingoes affect ecosystems and how different animals respond to human-induced changes to the environment.

He holds a courtesy faculty position within the Department of Forest Ecosystems and Society at Oregon State University and is an Affiliate Assistant Professor within the School of Environmental and Forest Sciences at the University of Washington.

According to Dr Newsome, an increased understanding of the relationship between body size and extinction risk would affect animal conservation, with different approaches needed for protecting larger versus smaller species.

“For the smaller species, freshwater and land habitat protection is key because many of these species have highly restricted ranges,” he said.

“For the large species there is an urgent need to reduce the consumption of wild meat to lessen the negative impacts of human hunting, fishing and trapping.

“But it’s ultimately slowing the human population growth rate that will be the crucial long-term factor in limiting extinction risks to many species.

“Based on our findings, human activity seems poised to chop off both the head and tail in the size distribution of life.”

Dr Newsome said such species loss would have a significant impact on the planet.

“Large vertebrates play an important role in structuring ecosystems. Many large-bodied vertebrates shown to be at-risk in our analysis are also predators, which influence food webs from the top down, and can affect environmental processes like disease, wildfire and carbon storage, and may even buffer communities from climate change.

“The fact that our research shows extinction risk is highest for large animals adds to growing concern that the loss of top predators will disrupt to delicate balance of the ecosystem.”

Dr Newsome said smaller vertebrates also played an important role, particularly in ecological functions that required a small body size, including the pollination done by bats and hummingbirds.

“Our findings highlight the danger of disproportionately focusing on the conservation of larger species, often the face of major fundraising efforts,” he said.

“In the past the vulnerabilities of smaller vertebrates has been underestimated, so this research shows the importance of conservation efforts for both the biggest and smallest members of the animal kingdom.”

Published by Deakin Research 19 September 2017