A new paper examines how the reliance of large predators on human-provided food impacts on ecosystems, human-wildlife interactions and the genetic diversity of predator populations.

Around the world, large predators, such as grey wolves and bears, are reoccupying their former habitats.

However, in their absence, the environment has often been modified by humans and contains an abundant supply of human – or anthropogenic – foods like garbage, livestock and carcasses left by hunters.

A new paper published in “BioScience” explores whether the availability of such food sources is modifying large carnivore ecology and the possible consequences for conservation.

According to the authors of “Making a new dog?” there are numerous examples of animals changing their social structure, movements and behaviour in order to access anthropogenic foods.

The study used grey wolves and other predators, such as red foxes and dingoes, as case studies to explore the implications of such change for ecosystem restoration efforts, human/animal conflicts and the possibility of unintentional domestication.

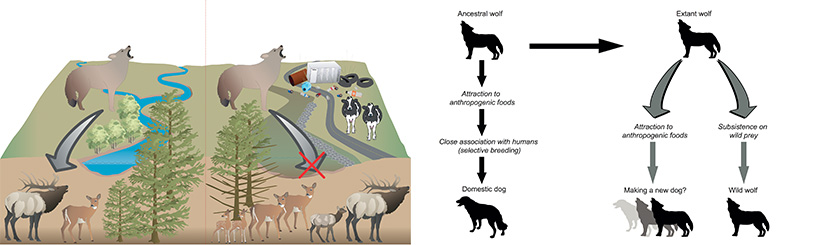

Left: A hypothetical comparison of grey wolf (Canis lupus) ecological effects in wilderness areas (left) and human-modified systems (right) where there are abundant anthropogenic foods. Original images courtesy of the Integration and Application Network, University of Maryland. Right: This conceptual model shows the role of anthropogenic foods in the hypothesised original wolf domestication pathway (left) and possible evolutionary divergence (right) due to behavioural and genetic differentiation. Silhouettes courtesy of Phylopic (Tracy A. Heath).

Lead author Dr Thomas Newsome, from Deakin University’s Centre for Integrative Ecology (CIE) and the University of Sydney, said grey wolves were the primary focus of the paper because they were the first animal domesticated by people.

“The date and location of wolf domestication is hotly debated, but the domestication process probably involved the initial steps of wolves being attracted to garbage and food scraps and then contact with people.

“It’s important to highlight this process because large quantities of anthropogenic foods are intentionally or unintentionally provided to animal communities around the world.

“Access to these foods has the capacity to change a variety of animal life traits, including genetics, social structures and behaviour,” he said.

Dr Newsome said research showed that at least 36 species of terrestrial predator more than one kilogram in body size used anthropogenic foods in 34 countries worldwide.

[testimonial_text]Where there is access to anthropogenic food, there are documented effects on predator abundance, dietary preferences, life-history parameters, and movements, as well as negative effects on co-occurring species that become more susceptible to predation[/testimonial_text]

[testimonial_picture name=”Dr Thomas Newsome” details=”Centre for Integrative Ecology”]

[/testimonial_picture]

[/testimonial_picture]Dr Newsome, who studied dingoes in Central Australia for his PhD, and populations of grey wolves in the US as part of his post-doctoral research, explained that access to anthropogenic foods contributed to the “founder effect,” where small groups become attracted to a particular food source and stop breeding with other groups.

This limits genetic diversity and leads to separate, distinct population clusters.

“These animals may have different behaviours to others of their species; they typically have smaller home ranges and may develop a larger body size when they have easy access to large quantities of anthropogenic foods,” Dr Newsome said.

He said apex predators like dingoes and wolves interacted with so many aspects of the ecosystem that changes in their behaviour caused by access to anthropogenic foods could have profound effects.

Image Credits: (left) Garry Weinert, (right) Doug McLaughlin

“The availability of anthropogenic foods may alter the ecological relationships of wolves, both within their species and with other species.

“Our research suggests that where anthropogenic foods are abundant, the ecological effects of wolves will differ from those in systems with low or no human presence or effects,” Dr Newsome explained.

However, according to the paper’s authors, despite the likelihood that these changes could affect ecosystem health, it is rarely acknowledged that the availability of anthropogenic foods “is a global conservation issue and could possibly be the starting point for domestication of wild species.”

Dr Newsome and his fellow authors have called for further research into the specific characteristics and population structures of wolves and other large predators in areas of strong human influence, especially where animals rely heavily on anthropogenic foods.

“Developing an in-depth understanding of how human induced alterations of the environment might shape the evolution of species and affect ecosystem functioning is vital for how we conserve and manage our world,” Dr Newsome said.