From a recent presentation by Prof Shahram Akbarzadeh at the Federation of Ethnic Communities’ Councils of Australia’s (FECCA) conference.

Citizenship in Australia has become a hot political topic.

It’s now used as an instrument of political point scoring and populism.

Some political leaders, mostly on the right, see citizenship as the Holy Grail; the ultimate prize bestowed on people who have demonstrated their worthiness, excluding those not worthy of being called Australian.

But that is a counter-productive and extremely harmful approach to citizenship.

Becoming a citizen by pledging an oath of allegiance to this land should not be seen as a prize–one that is outside the reach of new migrants – but as a logical step towards greater integration.

The latter approach is consistent with Australia’s history of multiculturalism and valuing diversity, both of which have come under severe strain in the recent past.

Red tape sends a clear signal

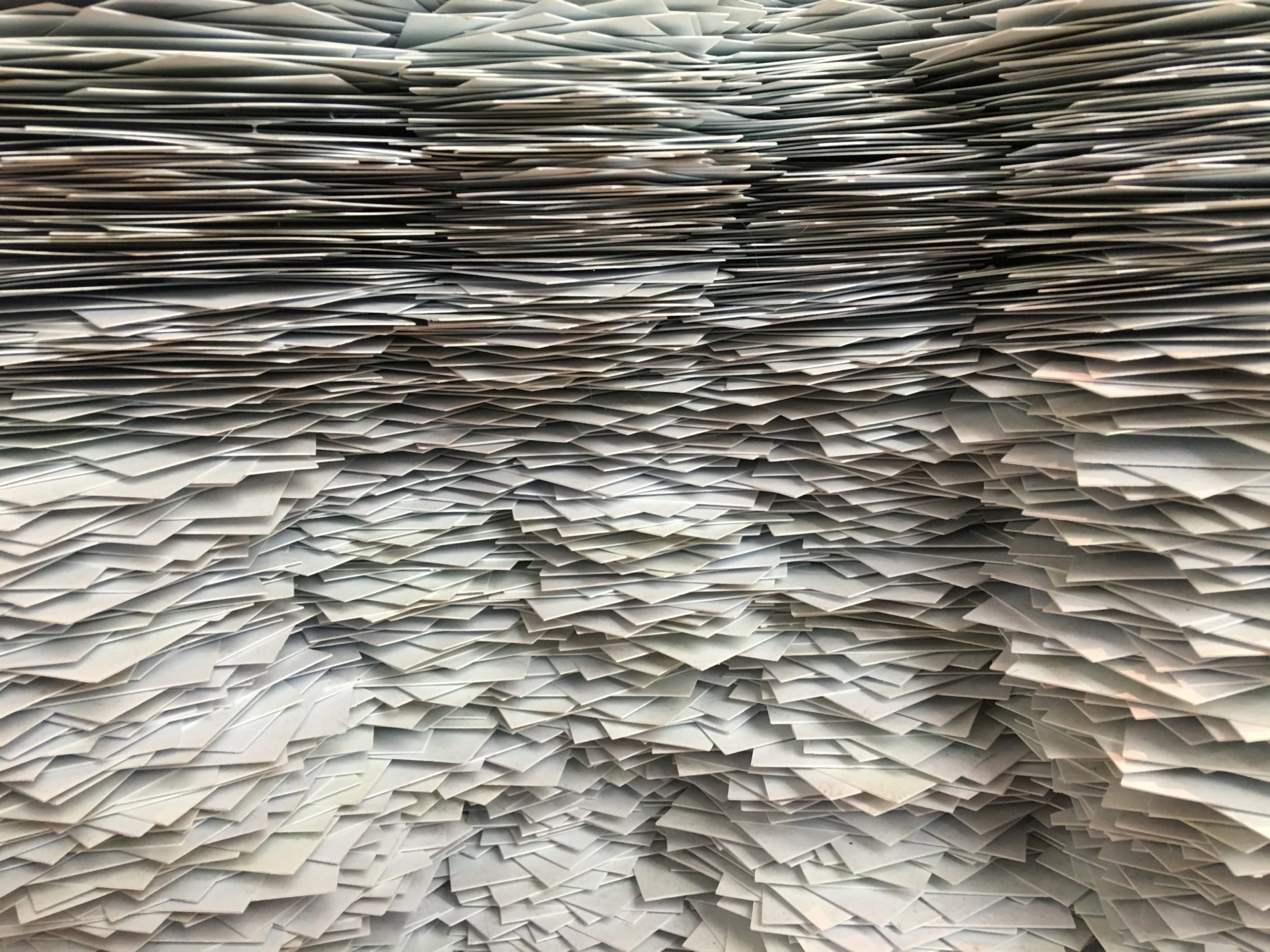

In a recent audit report of the citizenship process, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) found the Department of Home Affairs handling of citizenship applications to be inefficient, pointing to a serious “decline in processing performance.”

That’s official language for a system that effectively keeps citizenship applications in a locked drawer for months.

Over the past four years, application numbers waiting to be processed have increased by more than 700 per cent.

They simply pile up without being processed.

Citizenship application by conferral should take no more than 80 days. But according to the audit report, more than 80 per cent of the cases took up to 337 days from lodgement.

That’s more than four times the former standard.

What is even more disturbing is that the processing time for applications by refugees took even longer, some took twice as long.

On average, citizenship applications by former refugees took 682 days – the majority of whom had come from Afghanistan, Sri Lanka and Iraq.

This is a disturbing picture and points to a deliberate delaying tactic through administrative means. The red tape surrounding citizenship applications sends a clear signal.

A signal that is directed at two very different audiences.

To the applicants, it says; if you are brown or Muslim you will have a long wait. We don’t really want you and will do everything to make it difficult for you to gain Australian citizenship.

That message is even louder for refugees.

And if this sounds somewhat familiar, it’s because we have heard similar claims of seeing Muslims and brown people as a threat to Australia’s national security from the political Right.

The message for the political camp on the Right; we sympathise with you when you oppose accepting non-European migrants and when you see them as a challenge to the idealised White Australia.

A matter of border protection and national security?

Hiding behind the motto of national security is an expedient claim that is quite common for the political Right.

In early 2018, Pauline Hanson produced a private member’s Bill before the Federal Parliament to increase the waiting period for permanent residents to eight years before they could apply to be Australian citizens.

She justified the long waiting period in terms of physical and cultural security. Pauline Hanson insisted that migrants need to prove they are “not criminals” and loyal to Australia.

In her words:

“Because once these people become an Australian citizen, we cannot get rid of them if they are a bad character, want to go and fight for ISIS, or if they are actually criminals. So I think we need to toughen our laws and our borders.”

Acquiring citizenship for migrants is tied to border protection and national security, the same motto that has been used to challenge migration from Muslim countries and send asylum seekers to off-shore processing facilities.

The sense of moral panic that reverberates through such statements is extremely damaging to the social fabric of Australia. Some political actors might think they can benefit from weaponizing access to Citizenship.

But any political gains they achieve are short-lived.

If the Liberal/National Coalition Government thinks that by kowtowing to the Right, and borrowing from their xenophobic platform, it can disarm the Right and gain the political upper-hand, it is sadly mistaken.

Australia cannot shut itself out of the world

Research has shown that such acts of “borrowing from the Right” only emboldens the Right and increases the pressure on the incumbent government.

That’s what we are seeing in Australia.

A gradual shift to the right because the incumbent leaders are too worried about not being seen as tough on national security matters.

This betrays a lack of vision for Australia on how it can capitalise on its rich diversity – a vision of a multicultural, multi-ethnic and multi-faith society that can push in the same direction.

Multiplicity of origins does not detract from common purpose and a shared vision.

Australia has prospered on the toil of its migrants, especially in the late 20th century, some with very little or no English. But these migrants subscribed to the vision of making Australia a vibrant, fair, prospering country, providing a better future for their families.

That vision and commitment has been integral to Australia’s multiculturalism, which, unfortunately, has been under attack from the Right.

Australia’s multiculturalism has been a response to the realities of the day; a recognition of the fact that Australia cannot shut itself out of the world, and that the Australian economy desperately needs the injection of labour force that migrants bring.

Multiculturalism has also meant that migrants don’t have to turn their back on their language, traditions and heritage to contribute to Australia. In fact, multiculturalism is a celebration of diversity, cherishing the differences that enrich us.

The policy of multiculturalism is not about ghettoization of migrant communities, but about offering the time and safe spaces for ethnic communities to settle and grow roots here.

Becoming a citizen by pledging allegiance to Australia for migrants is an extension of the same process of accommodating integration.

But the changes brought on by the 2007 Citizenship Act have been a paradigm shift that broke with multiculturalism and sought to impose expectations of assimilation on migrant communities.

While the political leaders in the Liberal-National Coalition are careful not to explicitly use the term, assimilation has gained significant sway in the way they see migrants and their future in Australia.

And while the Federal Labour Party has been more vocal in its defence of multiculturalism and cherishing diversity, it shied away from repealing the 2007 Citizenship Act.

Linking this with National Security and the moral panic that claims Australia is being swamped by Asians, or Muslims, the new Citizenship regime expects a much higher level of assimilation.

And by extension, it presents diversity as a challenge, even a threat to Australia.

This paradigm shift is most evident in the treatment of Australian Muslims.

While xenophobia and Islamophobia are not new, they have been inextricably linked to the panic of the “war on terror”, which depicted Muslims as a whole as potential terrorists.

This is a view that has flared up again in response to the handful of Australian Muslims who joined ISIS in Syria.

The broad-brush approach to Muslims and the assignment of guilt by association has done immense damage to community relations and trust.

This is most evident among Muslim youth who feel rejected and alienated. It is not difficult to see why so many Muslim youth question their future in Australia.

They say, “if you don’t want me to be here, why should I bother pleasing you?”

Disengagement and alienation are real challenges. This is a dangerous dynamic that can tear at the very fabric of Australia.

I’d like to conclude with a warning, regarding the direction we have taken.

The multicultural model and citizenship laws before the introduction of the English language test and the knowledge tests provided for the integration of communities into the mixed Australian family is vastly different to this new assimilation model.

This creeping assimilation model aims to exclude “unworthy” people and their culture. The administrative delays in processing citizenship applications are simply a manifestation of this paradigm shift that can only be challenged openly in the public domain.

Research has shown that migrant communities have much greater willingness to integrate and show greater commitment to their countries of adoption when they feel valued and respected.

When they don’t feel pressured to put aside their history and culture to be accepted.

Acquiring citizenship is a logical step in the process of integration. It’s an important step, which many migrants are proud to take.

On the other hand, the assimilation agenda feeds resentment and a sense of insecurity among target communities. It creates an underclass of residents who are not seen as “good enough” to be called Australian. And that can be a source of angst and disappointment.

Now we are seeing cases of Muslim youth internalising that sense of “not belonging” here. This is a great challenge that will get worse as we are pushed more and more along this trajectory of Right-wing populism.

But all is not lost.

Stepping back from the brink is possible and desirable for the future of a tolerant and vibrant Australia.

Stepping back requires coalition building, coordination and public education by community organisations and public institutions – like universities – in articulating the benefits and rewards of a multicultural Australia.

A recognition of diversity as an invaluable asset.