“The winding path is just how a path is, and therefore it needs no name.”

The simplicity (and honesty) of this sentence belies the complexity of the ideas surrounding it.

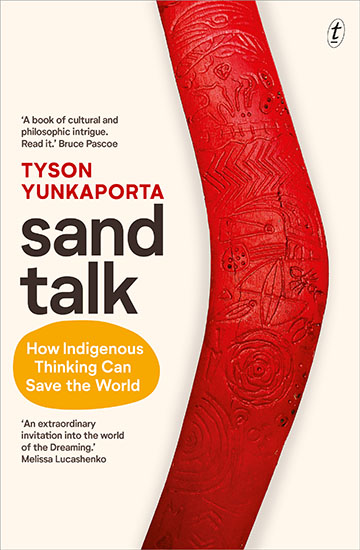

It’s something that Indigenous author and Deakin University Senior Lecturer of Indigenous Knowledge at the Institute of Koori Education, Tyson Yunkaporta, wishes to highlight in his new book Sand Talk: How Aboriginal Thinking Can Save the World.

The quote is an explanation for the Aboriginal notion of time. The word ‘non-linear’ is Yunkaporta’s best, but imperfect, attempt at a descriptor.

“We don’t have a word for non-linear in our languages because nobody would consider travelling, thinking or talking in a straight path in the first place. The winding path is just how a path is, and therefore it needs no name,” he says in the book.

Sand Talk: How indigenous thinking can save the world

Sand Talk, Yunkaporta says, is a reversal of the western approach to writing – “rather than reporting on Indigenous Knowledge for a global audience, I’m looking at global systems from an Indigenous Knowledge perspective.”

By highlighting (and celebrating) the complexity of Indigenous Knowledge, Yunkaporta connects the Indigenous culture with ideas of complexity theory – the rejection of the linear, mechanical way of thinking that looks to “deal with the natural and artificial systems as they are, and not by simplifying them (breaking them down into their constituent parts).”

Throughout the book, he employs an Indigenous pronoun that doesn’t exist in English – the idea of ‘us-two’.

“I’m constantly referring to myself and the reader us ‘us-two’ like a kinship pair. And encouraging [the reader] to form other ‘us-two’ pairings and work with each other and represent knowledge in that way,” says Yunkaporta.

“But there’s also the ‘us-exclusive’ which is just us, not them. You have exclusive groups. But then you also have to have those groups working with other groups, so there’s also an ‘us-all’ pairing,” he says.

“A lot of these things align with complexity theory.”

It is here, Yunkaporta says, rather than reducing Indigenous Knowledge down to a series of symbols and codes for ease of understanding, and released from the linear, Newtonian way of thinking (encompassing notions of rationalism, cause and effect, time and, perhaps especially, the western ideas of the natural world) that Indigenous Knowledge can tackle one of the biggest challenges facing our world – climate change and sustainability.

It may seem like an ambitious title, but Sand Talk: How Aboriginal Thinking Can Save the World, should not be mistaken for being flippant.

In fact, Yunkaporta believes the complexity of Indigenous Knowledge is a fitting challenger for the complexity of the sustainability and climate change issues we face.

“Our knowledge endures because everybody carries a part of it, no matter how fragmentary. If you want to see the pattern of creation, you talk to everybody and listen carefully.

“Authentic knowledge processes are easy to verify if you are familiar with that pattern – each part reflects the design of the whole system,” he says.

Yunkaporta is quick to point out that his new book is “not the complete picture. What they’re reading is just a translation of a fragment of the knowledge.”

He is hyper-aware that the simple act of writing a book (in English no less) does not align to the oral practices of his Indigenous culture. It is limiting the expression of living, breathing ideas to the rigidity of the page.

Challenges in translation and adaptation

This poses a challenge for Yunkaporta, and all Indigenous writers and researchers really, where (in order to share ideas beyond their own communities) the oral Indigenous culture they exist in must express itself in the western, literary culture that has been imposed on them.

“The title Sand Talk is referring to the way of transmitting knowledge in Aboriginal cultures – drawing images on the ground,” he says.

“They then contain terabytes of information that you communicate with more than just words.”

To tackle the challenge of adapting oral culture processes in the creation of print-based works, Yunkaporta employs a cultural methodology called umpan.

“Each chapter is a series of thought experiments or yarns that happen with different people, but then the outcomes of those yarns are carved into a traditional object and that is the chapter captured in there,” he says.

“Umpan is the word for making or cutting or carving but it’s also a word that’s been adopted for writing. So writing is sort of seen the same way.

“I make sure that everything I write, I carve it first. And that preserves the oral culture orientation of my thinking.”

While each chapter is captured in an individual carved object, the entire book is also carved onto a large boomerang – which features on the book’s front cover.

“So I can hold that boomerang and pretty much recite that whole book. It sort of shows the way knowledge is encoded. Each of our objects, they’re not just these decorated, superstitious kind of spiritual things but they’re actually memory-inspired.”

A range of diverse influences

Although being born in Melbourne, Yunkaporta moved to Western Cape York when he was young and now belongs to the Apalech clan, with ties to mobs across WA and western NSW.

He began his career as a school teacher, teaching for 10 years before becoming an education consultant.

Along the way he has accrued a couple of masters degrees, then completed his doctorate in Education, with a focus on Aboriginal Pedagogies.

Yunkaporta has taken an interdisciplinary approach to his career in research, working across areas of education; ethics; digital communications; health and medicine; land management; astronomy; chemistry; Indigenous Knowledge and cognitive psychology.

Entangled rather than separated from his research career, Yunkaporta also takes on roles such as Indigenous thinker and community member, maker (of traditional wood carvings), art critic, poet and family man.

Sand Talk is a melding of these influences; a natural release of the combination of this professional and personal life, poured out on the page.

But don’t assume that what’s offered is a closed, idiosyncratic or personal viewpoint.

By employing the ‘us-two’ pronoun throughout the text, Yunkaporta asks the reader to emotionally connect with not just the text but to the author through the text.

It’s a connection that links back to the oral form that the text itself originated from.

A way of passing on the inherent orality of the knowledge conveyed in the book, bringing “print based and oral culture knowledge together in interesting ways,” says Yunkaporta.

“One of the whole premises of the book is that the knowledge is co-created with the reader. That we’re forming a kinship pair. So the idea is that they take it and grow it from there.”

It is also symptomatic of the non-linear (for want of a better word) nature of Indigenous culture.

As Yunkaporta says in the book, “What I say will be still be subjective and fragmentary, of course, and five minutes after it is written it will already be out of date – a problem common with all printed texts.

“The real knowledge will keep moving in lands and Peoples, and I’ll move on with it.

“You’ll move on too.”

The hope is that, after reading the book, you move on with a drive to add and expand on the knowledge that has been shared with you.

Tyson Yunkaporta’s book Sand Talk: How Aboriginal Thinking Can Save the World, was released on the 3rd September 2019 through Text Publishing.