Deakin University’s Associate Professor Melinda Hinkson has contributed to the placement of indigenous drawings on an elite UNESCO register.

A collection of 169 crayon drawings collected by noted anthropologist Mervyn Meggitt, while undertaking fieldwork with Warlpiri people at Lajamanu (Hooker Creek) in the northern Tanami Desert between 1953 and 1954, has been inscribed on to a list of just 57-precious items in Australia.

The UNESCO “Australian Memory of the World” list honours documentary heritage of significance for Australia and the world, and advocates for its preservation.

Associate Professor Melinda Hinkson, an anthropologist within the Alfred Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalisation (ADI), played a key role in revealing the significance of the drawings. She curated an exhibition at the National Museum of Australia in 2014 and wrote an associated book, called “Remembering the Future: Warlpiri life through the prism of drawing.”

Originally from Melbourne, Associate Professor Hinkson was based at the Australian National University for 15 years. She returned to Melbourne to join the ADI in 2015.

“I am delighted to see that my research has had this sort of impact,” she said. “The UNESCO inscription recognises the international significance of these drawings.”

Her research with the Warlpiri drawings has been recognised as breaking new ground in visual scholarship.

“Rather than viewing the drawings as artworks, I was interested to approach them through the wider lens of visual culture. I was trying to understand the larger historical and cross-cultural circumstances in which the drawings were made, as well as their importance in the present. The collection as a whole is like a time capsule, beguiling but also full of mystery,” she said.

Mervyn Meggitt, the anthropologist who collected the drawings, did not write about them and he destroyed his research materials prior to his death in 2004. So Hinkson had to undertake some careful detective work. She deployed a variety of methods in order to excavate their significance, including archival research, ethnographic work with descendants of the men and women who produced them, as well as the making of new drawings as a medium for reflecting upon large scale social transformation.

As she introduced the 1950s drawings to a new generation of Warlpiri unaware of their existence, Hinkson was fascinated by the way the drawings sparked discussions about contemporary concerns and fears, as much as they cast people back to an earlier time. Viewing drawings as objects of visual culture, she suggests, makes you start to look at them from a variety of different angles and to understand images as “highly dynamic things in the lives of people”.

The drawings were made in the early 1950s just months after Warlpiri people were forcibly relocated to a new government settlement at Hooker Creek, hundreds of kilometres north of their ancestral lands.

[testimonial_text]The drawings give us insight into the things people were thinking about and what they cared about at a time of profound social turbulence.[/testimonial_text]

[testimonial_picture name=”Associate Professor Hinkson” details=”Alfred Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalisation”]

[/testimonial_picture]

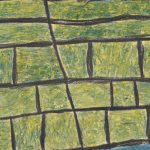

[/testimonial_picture]Produced in wax crayon on paper as experiments with colour and texture, they depict Dreamings and ancestral places, and the evolving architectural and social environment of the settlement. The Warlpiri Drawings predate the beginnings of the central desert art movement by two decades and include pictures that bear very little resemblance to the kinds of dot paintings Warlpiri produce for the art market today.

An important part of Hinkson’s research involved digital repatriation of the collection to Warlpiri communities, as well as sensitive negotiations to ensure Warlpiri men consented that the drawings be publicly circulated and made the focus of contemporary research.

Her current research extends her concern with displacement of Aboriginal people into the present. There is direct continuity from the biographical and historical work she did to unearth the story of the 1950s drawings and the work she does with Warlpiri in the present.

“As hunter-gatherers occupying an arid desert environment, Warlpiri people have always moved around,” she said.

“They were forced to move out of the desert from the 1920s onwards to make way for pastoralists and mining interests. I’m now interested in making sense of the contradictory nature of more recent imperatives to move. Warlpiri are profoundly open to the world, but in the present they are also under enormous pressure to pursue life choices that would take them further away from their country and kin and distinctively Warlpiri ways of living.

“In my current research I pose the questions, ‘When people are forced to move, what kinds of creative resources do they take with them? How do you continue to be yourself when the primary ground of your identity has been taken away?’ These are questions we tend to pose of migrant experience. I am beginning to understand something of the shared common ground between migrants and Aboriginal people.”

She sees the 1950s drawings as an example of how people living under severe pressure draw upon their internal creative resources in order to make sense of change and create a new place for themselves in turbulent circumstances.

The Warlpiri drawings, also known as the Meggitt Collection, are held by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies in Canberra. Acting CEO Craig Ritchie said the Institute was thrilled the drawings were being honoured through inclusion on the register.

“The drawings are truly beautiful to behold, the vibrant colours making them stand alone as artworks, without even considering their value to the Warlpiri people, or their historical and anthropological value,” Mr Ritchie said.

Photos are courtesy of Andrew Turner, AIATSIS (right) and AIATSIS (left and centre).