Wild weather in the Solomon Islands turned 3D ‘eco-printing’ into ‘extreme printing’ for a team of researchers from Deakin’s School of Engineering.

If you can print 3D plumbing parts in the middle of a cyclone, you can print them anywhere, according to Dr Mazher Mohammed, Senior Research Fellow with Deakin University’s School of Engineering.

His memories of this year’s trip to the Solomon Islands to trial unique 3D printing technology using recycled plastics include hugging a 3D printer to his chest to prevent it being blown away by cyclonic winds while his team held down the solar panels that powered it and chairs flew around their heads. They were three hours into a printing job and Dr Mohammed wasn’t going to stop the operation if he could avoid it.

“We found out the printers are incredibly waterproof and keep working when there’s no sun!” he laughed.

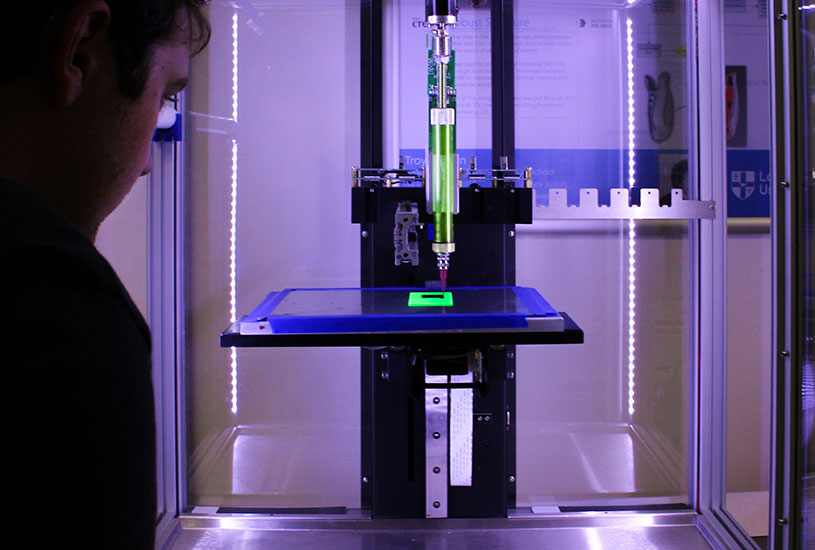

The trip was the next stage of a project with aid agency Plan International to develop solar-powered 3D printers that can produce plumbing parts using recycled plastics.

The project addresses a two-fold need to manufacture on-the-spot parts for fixing leaks in the Solomon Islands’ ageing water infrastructure and help reduce the plastic waste that litters the waterways and fills the rubbish dumps of the Islands.

During the ten-day trip to the capital Honiara and Visale – a village 40 kilometres away – Dr Mohammed and his team – Engineering Research Assistant Dan Wilson and engineering student Eli Gomez-Kervin – along with Plan International workers and local volunteers, tested every aspect of the system, trialling the printers’ abilities with different types of waste plastic, the effectiveness of the solar power system and how well the plastic parts worked in reality.

From left: Peter (local volunteer); Eli Gomez-Kervin, student at Deakin School of Engineering; Dan Wilson, Engineering Research Assistant, Deakin; Dr Mazher Mohammed, Deakin; Jamal, local Plan International partner at Solomon Islands Development Trust.

Unsure exactly what they would face in the Solomon Islands’ jungle, Dr Mohammed had left nothing to chance. The team arrived with two “heavily over-engineered” printers, a supply pack that would enable them to rebuild at least 60 per cent of a printer and a range of tried and tested pipe connector designs. The printers, for the most part, “ran like clockwork”, despite having to operate in high rainfall and extreme humidity.

“When we got back, we discovered rust just beginning to form on the bearings of one of the printer’s feed mechanism, due to the humidity. The material we printed with is also susceptible to moisture, so the more moisture it takes in the poorer the final product,” Dr Mohammed said.

“If we’d wanted to test everything in the harshest and most non-ideal circumstances possible – bar doing things underwater – we got them. And that was good, because ultimately these are the conditions the printers would be operating in and we figured if we can do it in a cyclone, high humidity and torrential rain, we can do it pretty much anywhere.”

The time in Honiara was spent scavenging for different types of plastic waste in local rubbish dumps and collecting e-waste – printer and computer parts – from offices in the area. These were washed and ground down into granules before being converted in a custom-built device into filaments for use in the 3D printers.

In Visale, where the lush jungle and ocean views made a picturesque backdrop to the cramped accommodations, the real test began. Could the 3D printed pipe connectors really stand up to the challenges presented by the village’s disintegrating water infrastructure?

Visale’s drinking water is provided from a catchment in the hills via a system of above-ground galvanised iron pipes through the jungle. When leaks appear, they’re repaired from whatever is at hand, including bamboo poles, poly pipes and inner tubes from old tyres, in order to keep the water supply going. It’s not always successful.

“The catchment is topped up by rainfall, but the continuous leaks in the system drain it to the point where it sometimes runs out altogether,” Dr Mohammed said.

3D printed pipes are making a difference in the Solomon Islands.

[testimonial_text]We identified one particular leak in a part that seemed to be made from two different types of hose and was gushing enough water for someone to shower under. Given how much potential pressure the pipe was under, we thought it would give us not only the biggest bang for our buck in saving water, but would test the technology to the nth degree.[/testimonial_text]

[testimonial_picture name=”Dr Mazher Mohammed” details=”School of Engineering Research Fellow”]

[/testimonial_picture]

[/testimonial_picture]“The village’s elder, Patrick, was sceptical at first – he thought we were just going to drive back to Honiara and buy a part. He and a few others from the village turned out to watch us print this part, before many of the villagers came to observe us fix the leak. The first time, the sizing was right, but there were leaks coming from between the layers. We reprinted it and made it a little thicker and this time there were no leaks at all.”

Two months later a team from Michigan University in the US, contracted by Plan International to conduct a business case study on the supply chain and costing of the project, visited Visale and found the part – printed from recycled ink cartridges and computer keyboards – was intact and still holding in the water.

The pipes weren’t the only things that leaked. The communal taps in the village did as well, so Dr Mohammed and the team found themselves designing and printing tap seals, too.

“Nearly every single tap was gushing water, and not just because someone had left it running. The volume of water was around a bucketful every two to three minutes, which was perhaps a larger drain on the water system than the leaking pipes. I thought, ‘let’s have a go at printing some seals’, and after four or five tries we managed to make one that worked. It wasn’t the prettiest thing to look at, but we managed to fix about three taps and save a lot of water.”

Dr Mohammed said it was an exercise in testing whatever plastic was to hand and discovering what worked best for different situations. Plastic from the ubiquitous e-waste was good for the pipe connectors. More flexible plastic from old jerry cans was best for the tap seals. The plastic from soft-drink crates turned out to have a second life as a filament perfect for weaving baskets and bracelets and as a cord for whipper snippers.

“This is what happens when you’re in the jungle with no Internet!” Dr Mohammed joked. “You come up with all kinds of ideas when people ask what else ‘that machine’ can do than print pipe connectors.”

He said as a trial run for the equipment and to discover how useful the project would be in reality, the trip was successful, but it also demonstrated the enormous scope of the problem.

“It backed up our original plan to create a way for people in the villages to have this tool and use it to make what they need, when they need it,” he said.

“However, we need to keep working on how we make the system more affordable and more user-friendly, and how we train people to use and maintain it. The Michigan University team also identified that the potential for the project has far more reach than only printing pipe connectors, in terms of social empowerment, education and sustainability.”

Dr Mohammed would like to acknowledge the contribution of Johannes Long and Callum Vidler, from Deakin’s School of Engineering, to the design and development of the technology involved in this project.

Watch more about Dr Mohammed and the team’s work in the Solomon Islands. Many thanks to Sam Thomas, Technical Officer – Digital Technologies, Deakin School of Engineering, for his work on compiling the footage for this video.

Read more about Dr Mohammed’s work.

Published by Deakin Research on 3 July 2018